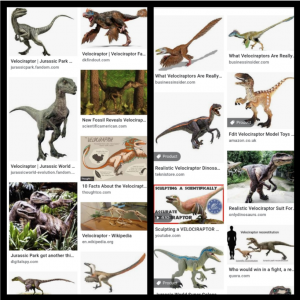

Last time, I was proposing that the Jurassic Park movieraptors could be viewed as sci fi cousins of the fantastical serpent-dragon. But out of all the dragons, the movieraptor bears the greatest physical similarity to the cockatrice, with the wyvern as a distant second. And since I have already mentioned Dilophosaurus, whose persistence could too be explained by reference to enchanting story tropes, I want to zoom out and explore the link between select Dinosaur Renaissance-style theropods of Jurassic Park and the cockatrice/basilisk in particular.

But before we can proceed, I need to mention that I have made some amendments to the definition of the movieraptor.

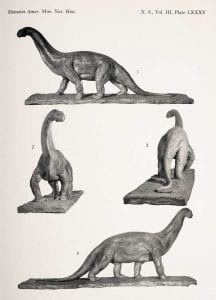

Carnosauriform: a carnivorous, bipedal dinosaur or dinosaur-like reptile rendered in the Dinosaur Renaissance style; scaly (entirely or largely), lean, usually shrink-wrapped in certain areas of its anatomy, and with hands, whose neutral position is pronated (downward-facing).

Movieraptor/Videoraptor: a carnosauriform with sickle claws on its feet and which can be classified as a member of the non-avialan Paraves. Usually, it hunts in packs.

This is because I had realized that the Jurassic Park Troodon (more on it in Part 2) essentially fits the description of the movieraptor as a scaly sickle-clawed dinosaur despite not being a dromaeosaurid.

Due to how bird-like paravians we are discovering them to be, and the real possibility of at least some of them being secondarily flightless, some ornithologists (e.g., Feduccia, 2013) and at least one palaeontologist (Gregory Paul, 2002) opted to call them outright birds. Perhaps Paraves, or even Pennaraptora (Paraves + Oviraptorosauria), might become a synonym of Aves (unless one is committed to a crown-group definition), so the movieraptor definition might be reformulated as a non-avialan, sickle-clawed bird rendered as a carnosauriform.

Now, let us know the basilisk a bit more. The earliest type, first described by Pliny the Elder (based on some actual small but most venomous snake of Nicander, 2nd century BC) as living in Cyrenaica (present-day Libya), has an unclear origin. One theory holds that is was based on the Egyptian cobra via stylized uraei of Ancient Egypt (Alexander, 1963). In that case, the basilisk’s white crown-like spot on the head may have come from sun disks on uraei and its killer gaze either from spitting venom or alleged powers of the uraei, which would have also have been the source of a poisonous breath (Alexander, 1963, pp. 171-173). This basilisk is enemies with and can be killed by the ichneumon, a weasel- or (rather) mongoose-like mammal. However, a novel hypothesis of Lenders and Janssen (2014) regards the basilisk as (based on) a grass snake, with the crown-like mark based on the species’ golden neck ring and its poison (whether in the gaze, smell, breath or hiss) being a Christian subversion of pagan beliefs tying the snake to land fertility; some medieval bestiaries link basilisks with agricultural dung heaps, where grass snakes lay their eggs (Lenders and Janssen, 2014). There is a discrepancy between the two views on how big Pliny’s basilisk was: four to six feet (Alexander, 1963) or only a foot long, too small to be even a hatchling cobra (Lenders and Janssen, 2014). Perhaps the king of serpents simply was dreamt of twice.

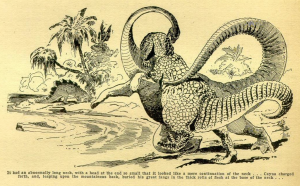

Whatever the origins of the first basilisk, a second emerged through illustrations of snakes with two wings and two legs, starting in the 10th century AD, and ending as a cock with a snaky tail by the 12th century (Alexander, 1963, pp. 175-176; Breiner, 1979, p. 30). This basilisk, sometimes described with a turkey’s neck and/or frog-like eyes, came to be known as the cockatrice, a French rendering of cocatris, one Latin variant for “crocodile”. How “cockatrice” came about has to do with the shifting meanings of the players of another story of Pliny, involving a crocodile having its belly eaten from the inside by another creature; this is a matter of bewildering confusion and I refer the reader to the work of Laurence A. Breiner (1979, pp. 30-36). Its rooster-like crest is due to the former basilisk’s mark being exaggerated by medieval writers (Alexander, 1963, p. 176).

Whatever the origins of the first basilisk, a second emerged through illustrations of snakes with two wings and two legs, starting in the 10th century AD, and ending as a cock with a snaky tail by the 12th century (Alexander, 1963, pp. 175-176; Breiner, 1979, p. 30). This basilisk, sometimes described with a turkey’s neck and/or frog-like eyes, came to be known as the cockatrice, a French rendering of cocatris, one Latin variant for “crocodile”. How “cockatrice” came about has to do with the shifting meanings of the players of another story of Pliny, involving a crocodile having its belly eaten from the inside by another creature; this is a matter of bewildering confusion and I refer the reader to the work of Laurence A. Breiner (1979, pp. 30-36). Its rooster-like crest is due to the former basilisk’s mark being exaggerated by medieval writers (Alexander, 1963, p. 176).

In the 16th century, the cockatrice-basilisk came to Poland and inspired the famous Warsaw legend. There, the cockatrice dwells in basements of the Krzywe Koło street and kills its victims by sight, meaning hardly anyone dares to descend underground or come out at night. Eventually, the death of at least one child provokes the people of Warsaw. They send a guy, sentenced earlier to death, clad in “armour” of mirrors to end the draconic monstrosity by making it glance at its own reflection. In one variant of the legend, the sentenced guy himself comes up with the shining armour (Sala, 2024, p. 77). In others, it is the idea of a brilliant scholar and the sentenced one simply volunteers (Oppman, 2008, Orłoń and Tyszkiewicz, 1988, pp. 100-102). In addition, either two unnamed children die (Orłoń and Tyszkiewicz, 1988, Sala, 2024) or a brother and sister are led to the basements by their mischievous friend, who is the one that died (the siblings managed to hide and survive) (Oppman, 2008).

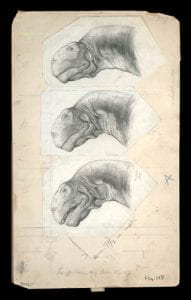

As we trace the evolution of Dilophosaurus in Jurassic Park the book and the film (Spielberg, 1993), we can observe some remarkable parallels to the origins of the first basilisk. Michael Crichton initially invented the venomous spit to account for the notch in the upper jaw that apparently weakened its bite (discussed in Brown and Marsh, 2021). Later, concept artist and puppeteer Mark “Crash” McCreery incorporated the neck frill into the design of Dilophosaurus (Stan Winston School, 2013, 0:26-0:37), evidently inspired by the frilled lizard. Interestingly, the frill is vaguely like the hood of the cobra, plus it rattles, the sound taken directly from the rattlesnake (Jurassic World, 2024, 1:02). While a departure from reality, these qualities give the Dilophosaurus (a.k.a. the Spitter) a serpentine gloss, potentially ensuring its rapid rise to stardom, as was probably the case with dragons of old.

Even so, Dilophosaurus has a unique character compared to the basilisk/cockatrice; the latter is always seriously deadly. In contrast, the Dilophosaurus was initially curious of Denis Nedry, even playfully hiding behind a tree. In that, it resembles more the lonely Gollum as he first met Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit (Tolkien, 1998). Of course, this cuteness serves to make Nedry’s final demise even more dramatic, but had Nedry been more courteous an

d less selfish (and had some food to offer), he might have won over the creature and keep it as a guardian pet.

Like the movieraptor before, the basilisk Dilophosaurus has established itself in the wider media. And this image has ossified by the time Marsh and Rowe (2020) updated the knowledge base through a complete re-description. Most significantly, the notch in Dilophosaurs’s upper jaw was found to be far more robust than previously believed, permitting to hunt even large sauropodomorphs (p. 27 of the study) and destroying any rationale for venomous capacity. Let us hope that another visionary sees that Dilophosaurus need not the mystical powers of the uraeus; sheer size and raw strength are enough.

References

Alexander, R. M. (1963) ‘The Evolution of the Basilisk’, Greece and Rome, 10(2), pp. 170-181.

Breiner, L. A. (1979) ‘The Career of the Cockatrice’, Isis, 70(1), pp. 30-47.

Brown, M. A. and Marsh, A. D. (2021) ‘The Real Dilophosaurus Would Have Eaten the Jurassic Park Version for Breakfast’, Scientific American, (no. 19/01/2025).

Cate, B. t. 2011. In: natrix.jpg, O.r.-g.s.-N.n. (ed.). Wikimedia Commons.

Feduccia, A. (2013) ‘Bird Origins Anew’, The Auk, 130(1), pp. 1-12.

Ghorayr 2011. Ouraeus (Naja haje legionis) – Egyptian cobra. In: Ouraeus.png, E.C. (ed.). Wikimedia Commons.

GoShows 2012. Reverse Side of Tutankhamun’s Throne. In: Throne.jpg, G.U.C.T.s. (ed.). My Flicker.com.

Lenders, H. J. R. and Janssen, I. A. W. (2014) ‘The Grass Snake and the Basilisk: From Pre-Christian Protective House God to the Antichrist’, Environment and History, 20(3), pp. 319-346.

Marsh, A. D. and Rowe, T. B. (2020) ‘A Comprehensive Anatomical and Phylogenetic Evaluation of Dilophosaurus wetherilli (Dinosauria, Theropoda) with Descriptions of New Specimens from the Kayenta Formation of Northern Arizona’, Journal of Paleontology, 94(S78), pp. 1-103.

MorphinESTP 2022. Mandalay spitting cobra (Naja mandalayensis). In: 2.jpg, N.m.C.L. (ed.). Wikimedia Commons.

Oppman, A. (2008) ‘Bazyliszek’, in Włodarczyk, B. (ed.) Legendy polskie. Krakow: GREG, pp. 23-34.

Orłoń, M. and Tyszkiewicz, J. (1988) Legendy i podania polskie. 1st, reprint edn. Warsaw: PTTK “Kraj”.

Paul, G. S. (2002) Dinosaurs of the Air: The Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinosaurs and Birds. USA: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sala, B. G. (2024) Księga smoków polskich. 2nd, reprint edn. Poland: BoSz.

School, S. W. 2013. JURASSIC PARK’s Spitter – Building the Dilophosaurus Dinosaur puppet. YouTube.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1998) The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. 5th edn. England: HarperCollins. Original publication in 1937.

Jurassic Park, 1993. Blu-Ray. Directed by Spielberg, S. United States: Universal Pictures.

World, J. 2024. Jurassic Park – Dinosaur Sounds with Gary Rydstrom. YouTube.

One of the most prevalent “what if” scenarios regarding prehistoric life, if not THE most prevalent, is the idea of how dinosaurs would have evolved if the massive asteroid never hit the Earth. Some are more grounded speculative evolution scenarios like the Speculative Dinosauria Project, while others are more “hard fantasy” worlds like Tales of Kaimere. However, one particular take on this “what if” comes in the form of the “Dinosauroid”. Created by Dale A. Russel in 1982, it depicts a Troodon/Stenonychosaurus as having evolved a very similar body shape to modern humans to occupy an identical niche. A steady increase in EQ, a very large braincase and eye sockets, and a language similar to bird songs were among its most notable traits. While an interesting and creative thought experiment, it’s been subjected to criticism from other paleontologists. Some accused it of over-anthropomorphization and misunderstanding of why humans developed their distinct body plans, with Darren Naish suggesting an “evolved” Troodontid would retain a more standard theropod plan. Such suggestions come into play with the real topic of this review. 25 years later, a children’s miniseries would be released with an alternate take on the “Dinosauroid” theory. Or in this case, “Dinosapien”. A series that is similarly charming and yet equally uncanny.

One of the most prevalent “what if” scenarios regarding prehistoric life, if not THE most prevalent, is the idea of how dinosaurs would have evolved if the massive asteroid never hit the Earth. Some are more grounded speculative evolution scenarios like the Speculative Dinosauria Project, while others are more “hard fantasy” worlds like Tales of Kaimere. However, one particular take on this “what if” comes in the form of the “Dinosauroid”. Created by Dale A. Russel in 1982, it depicts a Troodon/Stenonychosaurus as having evolved a very similar body shape to modern humans to occupy an identical niche. A steady increase in EQ, a very large braincase and eye sockets, and a language similar to bird songs were among its most notable traits. While an interesting and creative thought experiment, it’s been subjected to criticism from other paleontologists. Some accused it of over-anthropomorphization and misunderstanding of why humans developed their distinct body plans, with Darren Naish suggesting an “evolved” Troodontid would retain a more standard theropod plan. Such suggestions come into play with the real topic of this review. 25 years later, a children’s miniseries would be released with an alternate take on the “Dinosauroid” theory. Or in this case, “Dinosapien”. A series that is similarly charming and yet equally uncanny. Chances are, when you were a child, you thought dinosaurs were the coolest things ever. Giant reptiles comparable to creatures of myth and legend and the stars of some of the best (and worst) pieces of media of your childhood. And if you are a sensible person, that sentiment carried over into adulthood. Regardless of the quality of a piece of media, the presence of dinosaurs is an ideal way to get it at least some attention and at least a few fans. This is an example of what is called the “Rule of Cool”, in which creative liberties can be forgiven and one’s suspension of disbelief is increased if the media is sufficiently “awesome” or entertaining. Movies, books, and TV shows are typically what people think of when it comes to Paleo-themed “Rule of Cool” media, but one more underappreciated venue is video games, where the Rule of Cool can be turned up to 11. In the 90s and 2000s especially, before Trevorrow’s Jurassic World trilogy suffocated the paleo media genre for a time, there was a myriad of dinosaur-themed video games whose main selling point was emphasizing this rule, such as Turok, Dino Crisis (1 and 2), King Kong: The Official Game of the Movie, the extinct-animal themed packs for the Zoo Tycoon games, and too many Jurassic Park games (both good and bad) to count. Many of these have left strong legacies or at the very least gathered dedicated cult followings over the years, but there was one paleo-themed video game from 2006 that debatably represents the zenith of the “Rule of Cool” and yet has sadly fallen into near-complete obscurity: Paraworld.

Chances are, when you were a child, you thought dinosaurs were the coolest things ever. Giant reptiles comparable to creatures of myth and legend and the stars of some of the best (and worst) pieces of media of your childhood. And if you are a sensible person, that sentiment carried over into adulthood. Regardless of the quality of a piece of media, the presence of dinosaurs is an ideal way to get it at least some attention and at least a few fans. This is an example of what is called the “Rule of Cool”, in which creative liberties can be forgiven and one’s suspension of disbelief is increased if the media is sufficiently “awesome” or entertaining. Movies, books, and TV shows are typically what people think of when it comes to Paleo-themed “Rule of Cool” media, but one more underappreciated venue is video games, where the Rule of Cool can be turned up to 11. In the 90s and 2000s especially, before Trevorrow’s Jurassic World trilogy suffocated the paleo media genre for a time, there was a myriad of dinosaur-themed video games whose main selling point was emphasizing this rule, such as Turok, Dino Crisis (1 and 2), King Kong: The Official Game of the Movie, the extinct-animal themed packs for the Zoo Tycoon games, and too many Jurassic Park games (both good and bad) to count. Many of these have left strong legacies or at the very least gathered dedicated cult followings over the years, but there was one paleo-themed video game from 2006 that debatably represents the zenith of the “Rule of Cool” and yet has sadly fallen into near-complete obscurity: Paraworld. Stina Holmlund, and the wide-eyed Hungarian physicist Béla András Benedek are sent to this world by the leader of the SEAS (Society of Exact Alternative Sciences) Jarvis Babbit for what seems to be an expedition, only for them to realize that his real plan is to subjugate this Para-world as its ruler and seal off any future access by pushing the planet out of orbit via a massive jet engine inside a volcanic crater. For our heroes to stop the SEAs, they bring together the warring tribes and join forces with various disgruntled associates of the SEAs to help, including Babbit’s former assistant Ada Loven, engineer Nikolaj Taslow, naturalist James Warden, the Arch Druid, etc. So yeah, the game’s plot is incredibly derivative (See Avatar, Return of the Jedi, Last Samurai, etc), not to mention extremely dumb. It has plot holes you can drive a school bus through. But it’s also a story that’s not exactly meant to be taken seriously and it has its own corny charm to it. The game’s Rule of Cool factor also helps a lot. Action hero scientists leading warring tribes that ride dinosaurs and mammoths against robotic exo-suits and a giant jet engine inside a volcano is a sentence that is so over-the-top that it needs to be seen to be believed. In addition to this, if some of the aforementioned names seem familiar, a lot of the heroes are very on-the-nose expies of real scientists (Nikolaj Taslow for Nikola Tesla, James Warden for Charles Darwin, Jarvis Babbit for Charles Babbage, etc), but getting to have Darwin and Tesla fight alongside dinosaurs just makes the premise that much sillier to the point of being incredibly entertaining. It makes for both a good laugh and good dose of “Hell yeah”.

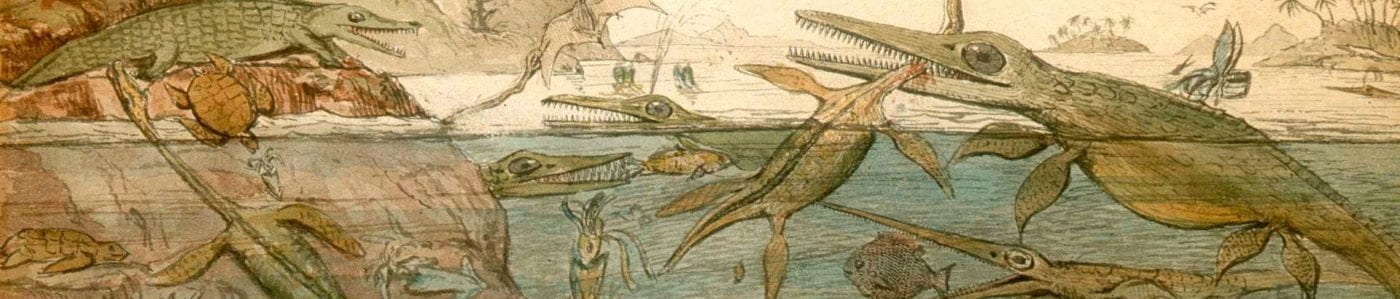

Stina Holmlund, and the wide-eyed Hungarian physicist Béla András Benedek are sent to this world by the leader of the SEAS (Society of Exact Alternative Sciences) Jarvis Babbit for what seems to be an expedition, only for them to realize that his real plan is to subjugate this Para-world as its ruler and seal off any future access by pushing the planet out of orbit via a massive jet engine inside a volcanic crater. For our heroes to stop the SEAs, they bring together the warring tribes and join forces with various disgruntled associates of the SEAs to help, including Babbit’s former assistant Ada Loven, engineer Nikolaj Taslow, naturalist James Warden, the Arch Druid, etc. So yeah, the game’s plot is incredibly derivative (See Avatar, Return of the Jedi, Last Samurai, etc), not to mention extremely dumb. It has plot holes you can drive a school bus through. But it’s also a story that’s not exactly meant to be taken seriously and it has its own corny charm to it. The game’s Rule of Cool factor also helps a lot. Action hero scientists leading warring tribes that ride dinosaurs and mammoths against robotic exo-suits and a giant jet engine inside a volcano is a sentence that is so over-the-top that it needs to be seen to be believed. In addition to this, if some of the aforementioned names seem familiar, a lot of the heroes are very on-the-nose expies of real scientists (Nikolaj Taslow for Nikola Tesla, James Warden for Charles Darwin, Jarvis Babbit for Charles Babbage, etc), but getting to have Darwin and Tesla fight alongside dinosaurs just makes the premise that much sillier to the point of being incredibly entertaining. It makes for both a good laugh and good dose of “Hell yeah”. By contrast, the nomadic Dustriders are incredibly flexible. Inspired by many nomadic African and Middle Eastern tribes in our own world, they can take down their buildings and retrieve the resources needed to build them back, allowing them to quickly dismantle their camps and move them to a more suitable location. Along with this reliance on mobility, the Dustriders are also specialized in cavalry, using massive dinosaurs such as Ankylosaurus, Stegosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus as powerful combat units that can be upgraded with coats of bone armor. Many of these dinosaurs can also be converted at will, so a Brachiosaurus can be quickly converted to an artillery unit with a massive catapult on its back to shoot poisonous rocks at buildings and then revert to a close combat unit in seconds. This even extends to their naval fleets. While they have long range catamarans, most of their naval ships are marine reptiles such as Macrochlemys and Kronosaurus.

By contrast, the nomadic Dustriders are incredibly flexible. Inspired by many nomadic African and Middle Eastern tribes in our own world, they can take down their buildings and retrieve the resources needed to build them back, allowing them to quickly dismantle their camps and move them to a more suitable location. Along with this reliance on mobility, the Dustriders are also specialized in cavalry, using massive dinosaurs such as Ankylosaurus, Stegosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus as powerful combat units that can be upgraded with coats of bone armor. Many of these dinosaurs can also be converted at will, so a Brachiosaurus can be quickly converted to an artillery unit with a massive catapult on its back to shoot poisonous rocks at buildings and then revert to a close combat unit in seconds. This even extends to their naval fleets. While they have long range catamarans, most of their naval ships are marine reptiles such as Macrochlemys and Kronosaurus. primitive weaponry, the SEAS have legitimate firearms such as muskets, machine guns and cannons. Additionally, they have steam-powered mechanical units ranging from motion-capture exosuits to vaguely dinosaur-shaped mechas, some of which are also equipped with machine and gatling guns. This is one area where even the “Rule of Cool” factor had to be sacrificed for the sake of gameplay. While seeing 20th century tanks and ships fight armies of dinosaurs would be the zenith of the “Rule of Cool”, it would only be for the short term. Realistically, the invading force with modern technology would have little difficulty wiping out more primitive tribes and the game required to make a few compromises to make it as fair as possible. Along with some questionable balancing (Gatling guns not melting down health in 5 seconds flat), 20th century weapons such as tanks and jets were not included and had to be replaced by the exosuits, things that dinosaur cavalry would have a fighting chance against. In addition, the tribes were equipped with their own tanks and heavy armor, which helps even the odds. While most of the game’s gameplay/story issues can be tolerated with “Rule of Cool”, they made the right call in sacrificing a bit of it to be as fair a fight as possible.

primitive weaponry, the SEAS have legitimate firearms such as muskets, machine guns and cannons. Additionally, they have steam-powered mechanical units ranging from motion-capture exosuits to vaguely dinosaur-shaped mechas, some of which are also equipped with machine and gatling guns. This is one area where even the “Rule of Cool” factor had to be sacrificed for the sake of gameplay. While seeing 20th century tanks and ships fight armies of dinosaurs would be the zenith of the “Rule of Cool”, it would only be for the short term. Realistically, the invading force with modern technology would have little difficulty wiping out more primitive tribes and the game required to make a few compromises to make it as fair as possible. Along with some questionable balancing (Gatling guns not melting down health in 5 seconds flat), 20th century weapons such as tanks and jets were not included and had to be replaced by the exosuits, things that dinosaur cavalry would have a fighting chance against. In addition, the tribes were equipped with their own tanks and heavy armor, which helps even the odds. While most of the game’s gameplay/story issues can be tolerated with “Rule of Cool”, they made the right call in sacrificing a bit of it to be as fair a fight as possible. So, this all begs the question: Why did the game fail? How did a game that is “Rule of Cool” personified become such a flop? Well, there were several factors. For one, it came out at a time where RTS games already had their day. By 2006, the genre’s peak in popularity with games like Starcraft, Warcraft 3, and Age of Empires was a distance memory and PC gaming was slowly being outcompeted by consoles such as Nintendo, Playstation and Xbox. It was extremely difficult for RTS games to carve their niche into the market at a time where first person shooters and open world games were gaining significant traction. So Paraworld had a severe case of bad timing. For two, when the “Rule of Cool” factor that the game relied on was peeled away, there wasn’t much left to help it stand out against its counterparts. Paraworld’s mechanics and gameplay loop, while smooth, was derivative of Age of Empires to the point that many reviews had pointed out the comparison. Even the Army Controller mechanic was a bit of a mixed bag. On the one hand, it allows you to properly micromanage your armies and check on each and every one of your units. But on the other hand, the limit of 52 units and the way it’s structured results in the battles being small in scale and limits what kind of armies you could make. These factors simply added up and created a recipe for commercial disaster and it resulted in a game that me and maybe 12 other people in the entire world still remember.

So, this all begs the question: Why did the game fail? How did a game that is “Rule of Cool” personified become such a flop? Well, there were several factors. For one, it came out at a time where RTS games already had their day. By 2006, the genre’s peak in popularity with games like Starcraft, Warcraft 3, and Age of Empires was a distance memory and PC gaming was slowly being outcompeted by consoles such as Nintendo, Playstation and Xbox. It was extremely difficult for RTS games to carve their niche into the market at a time where first person shooters and open world games were gaining significant traction. So Paraworld had a severe case of bad timing. For two, when the “Rule of Cool” factor that the game relied on was peeled away, there wasn’t much left to help it stand out against its counterparts. Paraworld’s mechanics and gameplay loop, while smooth, was derivative of Age of Empires to the point that many reviews had pointed out the comparison. Even the Army Controller mechanic was a bit of a mixed bag. On the one hand, it allows you to properly micromanage your armies and check on each and every one of your units. But on the other hand, the limit of 52 units and the way it’s structured results in the battles being small in scale and limits what kind of armies you could make. These factors simply added up and created a recipe for commercial disaster and it resulted in a game that me and maybe 12 other people in the entire world still remember. Survival Evolved serves as a clear spiritual successor, its lackluster gameplay mechanics, mixed bag of creature designs, infamously bad optimization, and lack of direction makes it a somewhat poor follow-up that fails to replicate Paraworld’s charm. Between its smooth, if derivative, gameplay, incredible musical score, appealing art direction, an entertainingly silly story and a nice variety of tribes complete with prehistoric creatures to lead into battle, Paraworld is the personification of the inherent “Rule of Cool” factor of paleomedia, for better and for worse.

Survival Evolved serves as a clear spiritual successor, its lackluster gameplay mechanics, mixed bag of creature designs, infamously bad optimization, and lack of direction makes it a somewhat poor follow-up that fails to replicate Paraworld’s charm. Between its smooth, if derivative, gameplay, incredible musical score, appealing art direction, an entertainingly silly story and a nice variety of tribes complete with prehistoric creatures to lead into battle, Paraworld is the personification of the inherent “Rule of Cool” factor of paleomedia, for better and for worse.

I was delighted to find my photograph Still Life with Fossil Seafood accepted for the Royal Academy “Summer” Exhibition this year. They say “summer” but it has only just opened to the public and goes on until 2 January. So, maybe more of a Devensian or Anglian summer, but with shorter days. However, when you go into the show it has the colour and energy of the brightest summer. It is also available to view online

I was delighted to find my photograph Still Life with Fossil Seafood accepted for the Royal Academy “Summer” Exhibition this year. They say “summer” but it has only just opened to the public and goes on until 2 January. So, maybe more of a Devensian or Anglian summer, but with shorter days. However, when you go into the show it has the colour and energy of the brightest summer. It is also available to view online

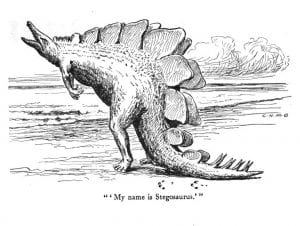

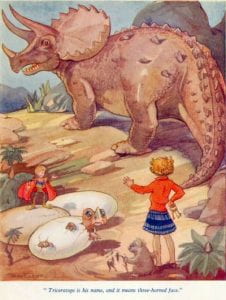

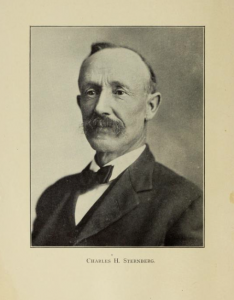

Sternberg’s prose is colorful. He paints vivid pictures that, although dated by today’s science, are evocative of a lost era. Here he describes the battle between a Trachodon and a Gorgosaurus:

Sternberg’s prose is colorful. He paints vivid pictures that, although dated by today’s science, are evocative of a lost era. Here he describes the battle between a Trachodon and a Gorgosaurus:

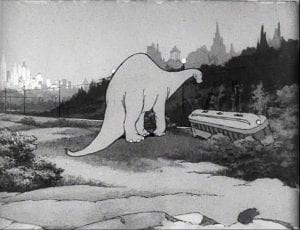

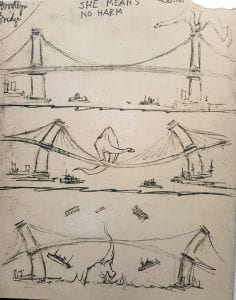

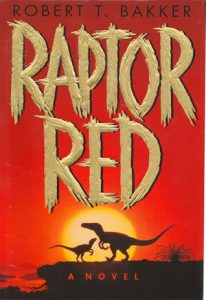

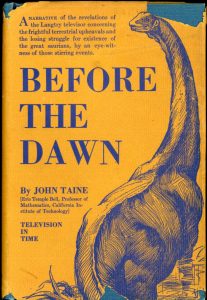

1934’s Before the Dawn by John Taine (pen name of Eric Temple Bell) is perhaps the first novel featuring dinosaur protagonists, predating Bakker’s novel by sixty-one years. The book’s prehistoric scenes are framed by scientists watching the beasts through some kind of time screen. One of the men has devised a means of replaying a residue of light within crystals just as someone might play grooves left by sound on an LP. The pseudoscience is beside the point, it’s just a vehicle to get to the dinosaurs.

1934’s Before the Dawn by John Taine (pen name of Eric Temple Bell) is perhaps the first novel featuring dinosaur protagonists, predating Bakker’s novel by sixty-one years. The book’s prehistoric scenes are framed by scientists watching the beasts through some kind of time screen. One of the men has devised a means of replaying a residue of light within crystals just as someone might play grooves left by sound on an LP. The pseudoscience is beside the point, it’s just a vehicle to get to the dinosaurs.