If you’re at all interested in dinosaurs, you’ll have seen the work of artist Charles R. Knight. His paintings and drawings have influenced generations of palaeoartists.

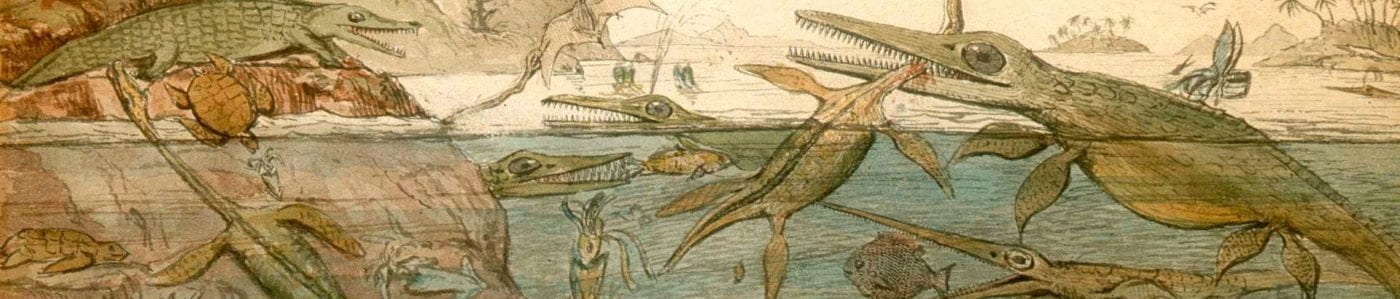

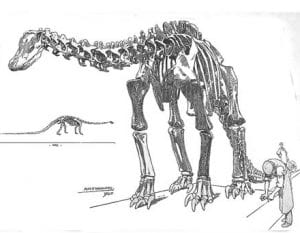

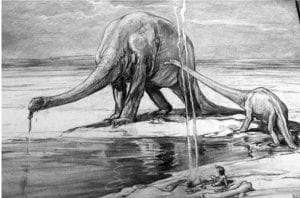

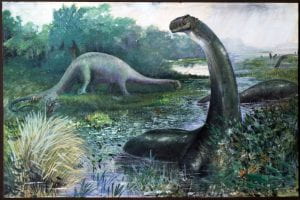

With the discovery of dinosaurs at the end of the 19th century, and the increasing number of species being found and named, the great museums of America started to show mounted dinosaur skeletons to the public. These were supplemented by painted reconstructions showing the animals as if alive, and Knight led the field in working with the museum scientists to make these reconstructions as accurate as possible.

Charles Knight (1874-1953) grew up in New York City, and developed a love of nature and animals from an early age. Encouraged by his parents, he learned to draw, at first copying pictures in books and visiting the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), which was then a single red-rick building in Manhattan Square. His father worked for J.P.Morgan, who financed the museum, and the family had special access to the museum outside visitor hours.

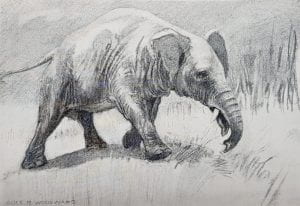

Charles already had been diagnosed with weak eyesight and astigmatism when, aged six, a friend threw a badly-aimed stone, which hit Charles in the right eye. It took months for him to regain any sight at all in that eye and put a strain on his left eye: he suffered from deteroriating eyesight all his life but he refused to let it stop him drawing. His love of animals and ability to draw can be seen in his drawing of the family dog, drawn at age 12.

In his teens he attended art school, including the Metropolitan Art School, held in the basement of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. From art school he was employed by a firm that made stained glass windows for churches where he worked on designs for the windows but when he was 18 his father died and, devastated, he left his job and went to live with his stepmother and grandparents. This didn’t last, so he moved back to Manhattan and worked as a freelance artist, illustrating children’s books and working for McClure’s magazine, but still spent time in the AMNH, where one of the museum scientists, Dr Jacob Wortman, asked him if he could paint prehistoric animals.

The result was this painting, of a large, pig-like mammal, Elotherium, which established Knight as the artist-in-residence at the AMNH, although keeping his freelance status. Here, he worked with Henry Fairfield Osborn, the curator of Vertebrate Paleontology, and Dr William Matthew to restore prehistoric skeletons and create paintings of them as if they were alive.

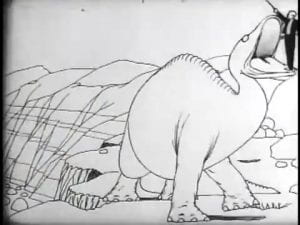

Osborn arranged for Knight to spend a few weeks with the elderly Edward Drinker Cope, the distinguished palaeontologist who had found and named many iconic and familiar dinosaurs and was, himself, something of an artist. The few weeks in Philadelphia made a great impact on the young Knight and influenced many of his paintings. One of the most famous to come out of this relationship was Leaping Laelaps, unusual for its depiction of dinosaurs as active and energetic during a time when they were usually thought of as slow, ponderous and reptilian.

Knight was to do most of his work for the AMNH, including watercolours and sculptures and many of his images were replicated for schools and students, but he was in demand by other museums, and in 1926 set off for Chicago to paint a series of twenty-eight murals for the new fossil hall of the Field Museum.

These became among the most well-known of Knight’s dinosaur pictures, but by then, his eyesight was deteriorating and he could only paint on small boards, to be enlarged by assistants who painted the actual murals.

His paintings were not confined to dinosaurs, he worked on prehistoric life in all its form, including murals for the AMNH’s “Age of Mammals in North America” in 1930, and three murals for Hall of the Age of Man showed how prehistoric humans lived. In the mid-1940s, Knight also painted for the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, a set of twenty-four small paintings showing life through different geological ages, but his longest association was with the AMNH.

Knight died in 1953. He had stopped painting two years earlier, having completely lost his sight.

William Stout’s introduction to ‘Charles R. Knight: Autobiography of an Artist’ states:

“If having a lasting influence on other artists is a key criterion for determining the greatness of an artists, then Charles Robert Knight is one of the most important artists of the twentieth century… Knight’s reconstructions became the basis for how dinosaurs were portrayed in the popular media – from King Kong, Fantasia and the animated films of Ray Harryhausen to the Disney theme parks. His paintings fired the ambitions of a legion of young people to choose palaeontology as their future profession. Charles R. Knight’s magnificent blend of powerful art and good science continues to inspire art, science and imagination around the world.”

References and further information:

- The World of Charles R Knight, http://www.charlesrknight.com

- Milner, R. Charles R. Knight: The Artist Who Saw Through Time. New York: Abrams, 2010.

- Knight, Charles R. Life Through the Ages: Commemorative Edition. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017.

- Knight, Charles R.; ed Ottaviani, Jim, Charles R. Knight: Autobiography of an Artist. G.T.Labs, 2005.