by Sophie Pollard, MSc Palaeobiology course, University of Bristol

(This post also shared on the Bristol Dinosaur Project blog)

No matter how much or how little you know about mythology, you know about dragons. They’re pretty much everywhere. From the feathered Quetzalcoatl of Aztec culture to the many-headed Mesopotamian deity Tiamat, supernatural serpents have been causing floods, kidnapping women, and making a general nuisance of themselves to the heroes of our favourite stories for as long as anyone can remember.

But where did these lumbering lizards come from in the first place? How did they get to be so widespread? And what does any of this have to do with palaeontology?

Well, when scientists took a look at the dragon myth from the perspective of evolutionary biology, they found some strangely familiar patterns. Myths tend to change gradually. Stories tend to get misremembered and changed in little ways with each telling, causing them to drift over time.

Maybe a fossil is discovered, and not knowing what to make of it, people assume it must be a dragon, adapting their myths to their new find, or perhaps accounts of unusual and terrifying animals get mixed up with mythology, or maybe the storyteller simply decides that the massive, serpentine predator just isn’t scary enough and adds an extra head or two for good measure.

You can look at these little changes in the same way you’d look at mutations in an organism, and the long-term drift of story elements in the same way as evolution. Adaptation in the face of a changing cultural environment. Survival of the coolest heroes, the scariest monsters, and the most satisfying endings.

And we can see real-life examples of this in the stories we still have today. Certain patterns and ideas, like an apocalyptic flood, cosmic hunt across the night sky and of course a scary, supersized snake are shared by many cultures across the world and tend to move around with human populations as they migrate throughout history.

To learn more about these patterns, mathematical methods can be borrowed from evolutionary biology. If we swap genetic or physical attributes of animals for the elements of a story, such as whether the dragon has mammalian features, or a taste for human flesh, we can use phylogenetic analysis to work out which patterns of development were the most likely, and even work out where a story might have come from in the first place.

In order to get so widely spread, you’d think the dragon myth would have had to appear pretty early in human history before we started to migrate around the world, or else it would have had to spring up on its own multiple times.

A group of scientists, led by Julien d’Huy, set out to determine the origin of the dragon using phylogenetic techniques in 2013. They used data from 23 regions around the world to create a number of “phylogenetic” trees, which could be combined to show which of the trees was the most likely.

The tests showed a very high likelihood that there was a single origin of the dragon myth. In fact, the trends shown in the research were stronger than those produced by most biological data, partially because they fit so well with patterns of migration in humans.

So, we can be pretty sure that the dragon has one single point of origin, and that it followed humanity as it dispersed around the globe. Furthermore, we now have an idea of what the myth looked like as it dispersed.

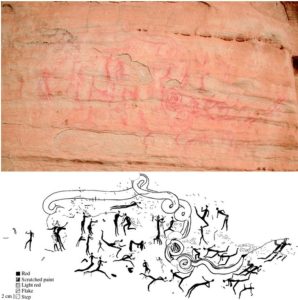

According to d’Huy and his research team, the first dragon story was likely being told as long as 75,000 years ago in South Africa. This dragon was a chimaera whose body was part snake and was linked with water in some way.

Interpretations of rock art from Lesotho, in southern Africa, seem to corroborate this story. One painting, in particular, termed the “Rain Snake Panel”, depicts men catching a gigantic, mythic snake in an underwater environment.

Human migrations out of Africa via the near east and into the far east would have carried the dragon myth with them, around 80, 000 to 60, 000 years ago.

At this point, the dragon was a giant snake, usually possessing the head of a second species, with ears, horns, scales, and sometimes human hair. It was still strongly associated with water, sometimes bringing storms, rain and floods, and could often fly.

These ideas will likely seem pretty familiar if you’ve heard any stories of eastern dragons. And you can even spot something similar in some early archaeological finds, such as the dragon depicted at the neolithic Xishuipo site in Henan, China, which dates back around 6, 000 years.

From here, the dragon made its way back towards the near east and up into Siberia losing many of its features and becoming more snake-like by around 50, 000 years ago. By this time, the dragon had also become increasingly more antagonistic and aggressive.

We then see the ice-age glacial maximum, allowing the Chinese myth to move a little ways south into parts of Oceania, and for the Siberian dragon to move into North America over the Bering land bridge, where we see the Palraijuq from Inuit oral tradition within the Yukon region of Canada.

This massive, crocodile-like monster is said to have had six legs and lived in lakes, streams, and swamps, where it would lie in wait for unsuspecting prey, dragging its victims into the icy waters to be drowned.

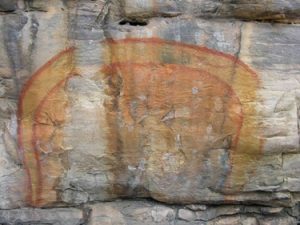

Meanwhile, the Chinese dragon myth headed down into Oceania but not quite all the way to Australia until the Younger Dryas event only 12, 000 years ago. Stories of the fabulously named Rainbow Serpent can be found all over Australia to this day, where it is often hailed as a creator deity in Aboriginal folklore.

Not long after, around 10, 000 years ago, the dragon myth crossed the Pacific Ocean to reach Mesoamerica. Quetzalcoatl, a feathered serpent and Aztec deity, which happens to have its own pterosaur, Quetzalcoatlus, named after it, is perhaps the most famous example of an American dragon.

We also see dragons all over Europe at this time, but they’re not the European dragons we see today. Instead, we see a giant serpent, usually with multiple heads, and the ability to speak as well as other human attributes. It lives in or near water, or sometimes underground, and is aggressive and dangerous, often with a taste for human sacrifice, but is also prone to trickery.

Around 8, 000 years ago, we see the Proto-Indo-European expansion, influencing Europe, India, western Asia, and North Africa (particularly the Nile region). The proto-Indo-Europeans spoke of NgWhi, who was a three-headed serpent who stole cattle, a resource which would have been extremely valuable to the people of the time.

Interestingly, and a little disappointingly, this taste for cattle may be responsible for the modern European dragon’s love of kidnapping women, due to a mistranslation of an old word for cow.

So, we have an idea of how the dragon myth found its way around the world, but that doesn’t explain why this idea stayed so popular for such a long time. After all, it’s rare to see any myth so widespread or so old.

The answer might lie in the simple fact that snakes are scary. Love them or hate them, we all jump a little when we see a suspiciously shaped stick out of the corner of our eyes. Humans have great snake-detecting capabilities, with brains designed to recognise visual patterns and three-dimensional, coloured vision. As a species, we are designed to hate snakes, so what better subject to scare each other with over a campfire?

We can never be completely sure where humans got the idea for dragons in the first place, or what drove it to take up so many forms all over the world, although we can make educated guesses. Either way, it’s nice to speculate on a subject so well-known and well-loved as the dragons of our childhood stories.

References

- Challis, S., Hollmann, J. & McGranaghan, M. ‘Rain snakes’ from the Senqu River: new light on Qing’s commentary on San rock art from Sehonghong, Lesotho. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 48, 331-354, doi:10.1080/0067270X.2013.797135 (2013).

- d’Huy, J. 2014.-2015. Statistical Methods for Studying Mythology: three Peer Reviewed Papers and a Short History of the Dragon Motif. – The Retrospective Methods Network Newsletter, Winter 2014-2015, 9, 125-127. The Retrospective Methods Network Newsletter, 125-127 (2014).

- Witton MP, Naish D (2008) A Reappraisal of Azhdarchid Pterosaur Functional Morphology and Paleoecology. PLoS ONE 3(5): e2271. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002271