In the genre of palaeoart which was – and still is – dominated by men, the sisters Alice Bolingbroke Woodward (1862-1951) and Gertrude Mary Woodward (1854-1939) were talented, professional illustrators of the Victorian and Edwardian periods. Their subjects ranged from children’s book to scientific illustrations of palaeontology, yet their scientific works are all but forgotten today.

The geologists among you will recognise the name of Henry Bolingbroke Woodward, FRS, the eminent geologist and palaeontologist, who eventually became president of the Geologists Association, Malacological Society and the Palaeontological Society. When not studying fossils, writing publications and attending meetings, he had time to father seven children. Two of his daughters, Gertrude and Alice, became professional artists, and although Alice became better known for her children’s book illustrations, both worked in scientific illustration, producing images for the Natural History Museum as well as for published works by scientists of the day.

The Woodward children were educated at home by a governess but from an early age all were encouraged and taught to draw and, while the boys went on to be scientists, the girls became artists.

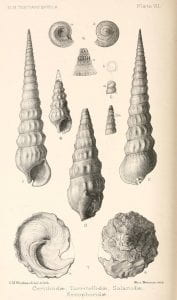

Gertrude mostly worked illustrating fossils and she created the images to accompany the infamous Piltdown fossils, a collection of bones that were found in 1912 and thought to be evidence of a formerly unknown early human. They were, in fact, a hoax, but this was not confirmed until 1953.

She became friends with Beatrix Potter, who was fascinated by palaeontology alongside her own childrens’ books and illustrations. Many of Gertrude’s drawings of fossils are in the care of the Natural History Museum, and she illustrated many of their publications on geology and palaeontology, although now her name seems to have faded into obscurity.

By her teens, Alice was being paid to illustrate her father’s lectures and his colleague’s papers. The money allowed her to attend art school, eventually studying at the Academie Julian in Paris, as well as receiving private tuition in illustration. Although working with children’s books, most famously illustrating The Peter Pan Picture Book by Daniel O’Connor.

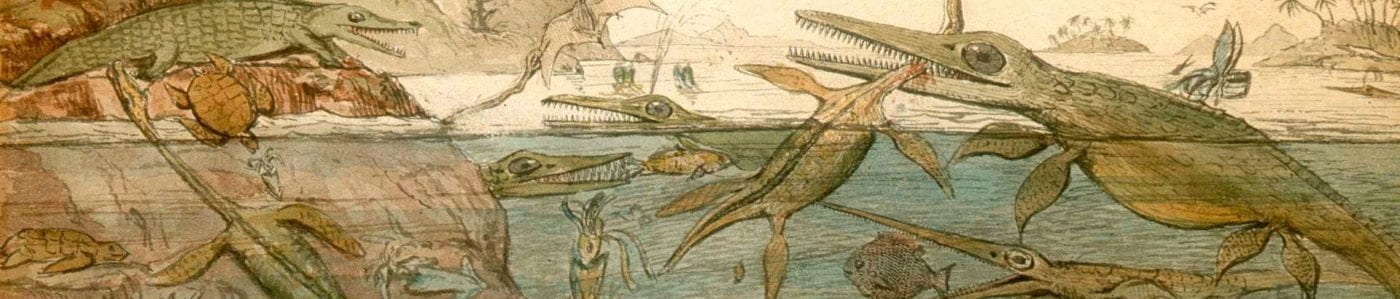

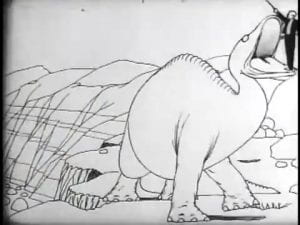

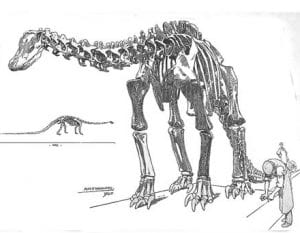

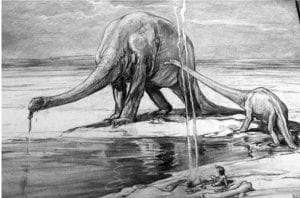

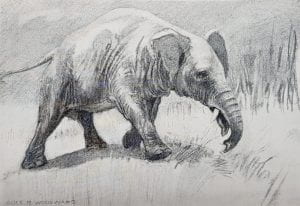

Her palaeontology illustrations, less well known, were considered accurate and life-like and ranged from recording fossils to reconstructing prehistoric creatures including dinosaurs. Her reconstuctions usually showed the subject in its environment, giving an overall effect of a living creature, and were highly regarded by the scientists commissioning them, although at times she added human figures into the composition; it was known that humans and dinosaurs didn’t co-exist but Alice used them to give an indication of scale.

Alice contributed to major publication by Henry Knipe, ‘Nebula to Man’ (1905), a substantial “coffee-table” book with 70 plates, which she co-illustrated with J. Smit, and ‘Evolution in the Past’, (1912), which had 50 plates, mostly by Alice.

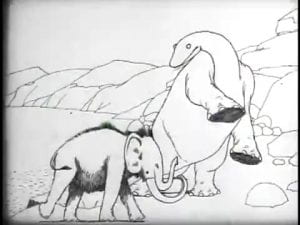

Three of her illustrations were used as plates in Hutchinson’s 1910 volume ‘Extinct Monsters and creatures of Other Days’, in the chapter illustrating the evolution of the elephant family; one image is shown here.

On her death, her sister Katherine arranged for her drawings to be sent to the Natural History Museum for safe-keeping, including five drawings of dinosaurs.

References:

- ‘Forgotten women in an extinct saurian (man’s) world’ SUSAN TURNER, CYNTHIA V. BUREK & RICHARD T. J. MOODY. From: Moody, R. T. J., Buffetaut, E., Naish, D. &Martill, D. M. (eds) Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 343, 111–153.

- ‘Dinosaur Sculpting’, Debus, A; Morales, B.; Debus, D., McFarland & Company, Inc, Jefferson, NC (2013)