A guest post from Benjamin Chandler, with many thanks to Benjamin.

We’re nearly at the end of August but there’s still time to squeeze in a good book before summer holiday is over. Usually summer reads feature people as protagonists—a quirky detective, an unfaithful Russian aristocrat, a wanderlusting whaler—but this is not always the case. Animals can take the protagonist’s role, too. Indeed, some of the first stories children hear have animal heroes instead of human ones, such as “The Three Little Pigs” or “The Little Red Hen”. Later, as children read on their own, they find beastly heroes in Black Beauty, Bambi, and Charlotte’s Web. Even as adults, readers engage with animal protagonists in books like Watership Down.

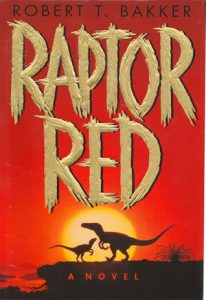

But what about prehistoric animals? Do they get to share the fictional limelight? Certainly! No doubt most folks in the paleo community are familiar with Robert Bakker’s Raptor Red, a novel following the life of a Utahraptor and the Cretaceous creatures that share her world. Bakker hoped the book would allow him to explore ideas about dinosaur behavior and help readers imagine these ancient creatures as living things. His characters hunt, sleep, fight rivals, build nests, and raise families, but also explore and play. One of the book’s most memorable scenes is of Utahraptors sliding down snowy hills in play much as corvids do today.

Bakker’s 1995 novel is just the most famous example of an author using prehistoric animals as their protagonists. Paleofiction has a legacy that reaches almost as far back as the popularization of paleontology.

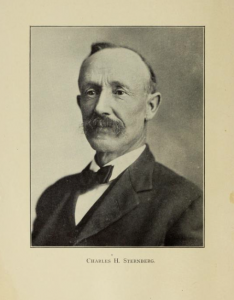

Charles H. Sternberg, an early 20th century fossil hunter and poet, composed several books about his discoveries, describing dusty Kansas chalk beds, horrific thunderstorms, and curious locals. In Hunting Dinosaurs in the Bad Lands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada (1917) Sternberg made his adventures less of the book’s focus and spends long passages describing antediluvian scenes. Chasmosaurs root in vegetation, ankylosaurs mow down meadows, and hadrosaurs of all manner wade through reeds and swamps. Sometimes Sternberg presents these scenes as imaginative reconstructions, other times these are described as dreams.

Sternberg’s prose is colorful. He paints vivid pictures that, although dated by today’s science, are evocative of a lost era. Here he describes the battle between a Trachodon and a Gorgosaurus:

Sternberg’s prose is colorful. He paints vivid pictures that, although dated by today’s science, are evocative of a lost era. Here he describes the battle between a Trachodon and a Gorgosaurus:

The noble lizard seeing that he could not escape his foe, bravely faces him. As if to hurry the end, he exposes the most vulnerable part of his body, by rising on his hind limbs. The enemy hurls himself at full length upon his defenseless victim; with great claws of hardened horn, full ten inches long, he rips his body down and red blood floods the mossy way. As he falls to earth and death, this tyrant, of those early days, tears open his body, and feeds on the quivering flesh and running blood in the very shelter of the redwood forest. The awful terror of the scene kept me well out of reach in the water. I was overcome with the shock, coming so swiftly in the peaceful woods. The sun was not darkened, the perfume of flowers filled the air, the gentle breeze sighed in the branches overhead, showing that nature knows no pity, no mercy. That death is inevitable, and still nature’s beauty, her changing seasons go on for time.

As can be seen in the paragraph’s end, Sternberg inserted himself into this story as an observer. He often pops up in his paleofiction passages to give a pithy comments about nature and God, or insert facts about various beasts’ lengths and weights, or note at which collections their bones now reside. He is clearly writing to inform as well as entertain. A rather touching length of the book features the ghost of Sternberg’s real-life late daughter. She comes to him in a dream of Cretaceous Kansas, and together they explore the beaches of the Niobraran Sea.

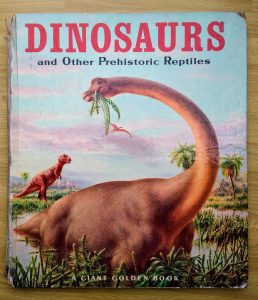

One of the most popular dinosaur books for several generations was Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Reptiles (1960) written by Jane Werner Watson and illustrated by Rudolph F. Zallinger. Much can be said about Zallinger’s illustrations; they are gorgeous, lush, and evocative, and likely what most readers remember of the book, but here we will discuss Watson’s text. Watson wrote dozens of children’s books, ranging from science books to Bible story retellings, from The Happy Little Whale to A Parade of Soviet Holidays. Her skills as an author are evident in Dinosaurs. Instead of dryly listing details about each animal and its environment, she composes stories that follow the actions of these creatures. The text matches the illustrations, sometimes extrapolating whole scenes from one image. For example, one of Zallinger’s paintings for the book features a troop of grouchy-looking Protoceratopses and a duo of lanky Oviraptors meeting over white sand and exposed nests of eggs. To pair with it, Watson wrote:

Watch! One egg, then another begins to quiver and crack. They are ready to hatch. The first baby crawls out. It has no bony cap as yet. That will come as it grows up. Now it is just very small and weak. And from the looks of things, it may not live to grow up. For here comes a hungry hunter.

The hunter is very small for a dinosaur, only about three feet long. Although he is hungry, meat is not the kind of meal he wants, for he has no teeth. Sucking eggs is his idea of a feast. This is why scientists of today call him Oviraptor, which means Egg Stealer….

The sky darkens. A cold wind rises. The wind sends stones rattling across the ground. It sends clouds of sand rolling and tumbling. Oviraptor feels the sting of the needle-like sand grains. He crouches on the nest, hiding his head. The sand slithers along. It piles up, drifting over the nest and eggs. It drifts over Oviraptor too.

The wind dies down. The sand settles. And now the desert is bare of life.

Watson’s prose, like Sternberg’s, is written in present tense, as if the reader was watching the scenes unfold. It is an effective way of bringing the reader into the images and the world they try to recreate.

But these tales are meant to inform as much as entertain. What about pure fiction without an educational mission?

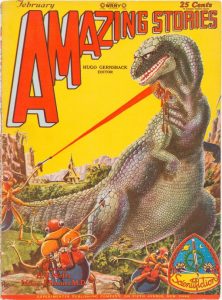

More than once the pulps published stories that featured dinosaur protagonists. Often these leaned heavily into violent melodrama. They were the pulps, after all.

“The Way of the Dinosaur” is one of these uber-violent tales. Written by Harley S. Aldinger and published in the April, 1928, issue of Amazing Stories, this story packs as much saurian slaughter into the text as possible. Cayna, a Tyrannosaurus, is the story’s focus and he is introduced thusly:

His little, red-rimmed, cold, reptilian eyes were blazing with hate and menace, for Cayna was in another of his blood-rampages that day, and woe betide the unlucky animals whom he encountered, no matter what their size and strength might be. It was a blood lust of a fierceness and wantonness, to which only Cayna could attain.

Cayna then storms across two and a half pages, killing a pterosaur, a Stegosaurus, a Triceratops, and a Brontosaurus before he himself is dragged under the sea by a gargantuan ichthyosaur. The story is mercifully short, for although the prose is amusingly purple and loaded with paleo-hyperbole—Cayna is “the most destructive living thing that ever existed”—the litany of dinosaur dismemberings and disembowelings gets tiresome. Violence for the sake of violence is not much fun to read.

More in the pulpy science fiction vein is “The Death of the Moon” by Alexander Phillips (Amazing Stories, February, 1929), in which another protagonist Tyrannosaurus thwarts an invasion of extraterrestrial insectoids. The bug folk are natives of the moon—a dying world during the Cretaceous Period. They set their sights on Earth and travel there, but their colonization attempt is crushed by the T. rex, thereby sparing the Earth for humans 65 million years later. Phillips gives the rex a dramatic death scene: “The sinking sun bathed the saurian’s grim visage in a soft, warm light and as he gazed into the last sunset he would ever see, across far spaces into the mellow glory of the Life-giver, Tyranosaurus’ eyes softened and he was vested with a dim, far-away dignity as one whose purpose is accomplished.” It’s a hero’s ending worthy of any summer blockbuster.

1934’s Before the Dawn by John Taine (pen name of Eric Temple Bell) is perhaps the first novel featuring dinosaur protagonists, predating Bakker’s novel by sixty-one years. The book’s prehistoric scenes are framed by scientists watching the beasts through some kind of time screen. One of the men has devised a means of replaying a residue of light within crystals just as someone might play grooves left by sound on an LP. The pseudoscience is beside the point, it’s just a vehicle to get to the dinosaurs.

1934’s Before the Dawn by John Taine (pen name of Eric Temple Bell) is perhaps the first novel featuring dinosaur protagonists, predating Bakker’s novel by sixty-one years. The book’s prehistoric scenes are framed by scientists watching the beasts through some kind of time screen. One of the men has devised a means of replaying a residue of light within crystals just as someone might play grooves left by sound on an LP. The pseudoscience is beside the point, it’s just a vehicle to get to the dinosaurs.

The scientists investigate the light memories of several crystals, letting them see a number of prehistoric scenes. A dinosaur hatchling survives a nest raid by a marsupial; several beasts scramble to escape a flash flood; sauropods laze in a weed-choked swamp; early birds flee burning volcanic ash. For the most part, none of the animals are named or identified, only described. It is up to the reader to recognize the species. (It could be argued that, if given access to time-TV, paleontologists would be hesitant to definitively identify species seen on the screen—after all dinosaurs are identified by their bones and age, things that would not be seen under the flesh and keratin in a visual recording.)

A group of theropods are named by the scientists, but instead of giving them names like Tyrannosaurus or Allosaurus, they call them Belshazzar, Jezebel, Bartholomew, and Satan. These four spend much of their time navigating curious rock formations, fighting each other over food, and jumping—lots and lots of jumping. Though all are given personality traits like greed, cowardice, and stupidity, Belshazzar is especially anthropomorphized. He is described as being the smartest of the four, and becomes the star of the crystal’s show.

Before the Dawn has been republished in pulps and anthologies, but, unlike as with some of his other stories, Taine did not let the copyright lapse. He must have been proud of this one.

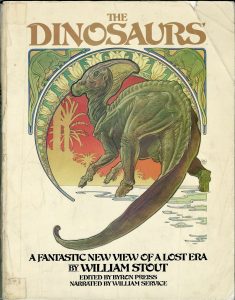

Pure paleofiction took a step out of lurid pulp and closer to poetry in 1981 when Byron Preiss published The Dinosaurs, William Stout’s famous “fantastic view of a lost era.” Preiss, impressed with Stout’s art, invited him to create a dinosaur book, which ultimately featured 130-some images. This was more art book than scientific screed. Although some folks might point out Stout’s penchant for “shrink-wrapping” his dinosaurs, this was the first major publication to show dinosaurs of the warm-blooded “Renaissance” galloping, tails lifted, partaking in activities beyond hunting and swamp-lounging. It was so outside the norm for a dinosaur book that it was featured in Life magazine.

Alongside Stout’s images are “narrations” by William Service. Preiss did Stout’s images right by linking them to Service’s prose.

Here Service describes a styracosaur’s morning:

When there was enough light to pick out the dark bare trunks of the magnolia grove, the ceratopsian came slowly awake. Massively fit, in the prime years of his life, nevertheless he struggled to his feet like one sick or wounded. Still percolating through his system were the juices from yesterday’s forage, when he had strayed from the herd to feed in a deadfall of cycad trees. In his mouth the texture of the moldering fronds lingered, on his tongue the strange taste of the foamy sap in the crowns.

Service was not pedantic with his facts, sometimes inventing behaviors—like Quetzalcoatlus mating styles—or name-dropping plants and critters that may have been anachronistic to the geologic moment, but he was just being as inventive with his stories as Stout was with his images. Service uses all manner of storytelling techniques to give each tale its own special flavor, adopting various tenses, points of view, emotional states, and humor. The dinosaurs not only feed and fight as they did in Sternberg’s and Watson’s stories, but also stumble, sleep, scratch itches, break wind, get sick, have sex, and poop. Service’s stories bring the Dinosaur from monstrous and mythic sagas to the everyday business of life.

Certainly the texts listed here are not the only examples of paleofiction. A popular series of children’s books published in the mid-80s by Rourke Enterprises recreated scenes from the lives of dozens of prehistoric animals. Each book told the story of one animal. Kids could read tales of Iguanodon, Nothosaurus, Dimetrodon, or a cave bear, to name a just few titles from the series. More recently the Smithsonian Institute published the “Prehistoric Pals” book series, which also told stories of ancient animals. Some of the series’s more amusing titles are Triceratops Gets Lost and Is Apatosaurus Okay? These two series are just a fraction of the picture books that have used paleofiction to bring dinosaurs and their ilk to life for kids. To list every publication would make this blog entry twice as long.

Natural history fires the imagination. That is perhaps its most exciting aspect. Above the details of how living things work, their measurements and metabolisms, is the fact that living things have lives. Humans may not share some of the hows of these lives—people do not lay eggs in ponds, fly on glassy wings, flutter tails to attract mates, or caress babies with a trunk—but all animals, human or otherwise, share the needs to eat, sleep, grow, endure disease, and reproduce. These experiences connect people with the natural world. People will never know the mind of a trilobite or a Tyrannosaurus or a Megatherium, but science can make an educated guess as to what their lives may have been like. Then writers can compose those lives and take a reader with them.