In 1900, a fifteen-year-old boy joined the staff of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Erwin S Christman had a passionate love of animals and was put to work making illustrations of fossil mammal skulls in the Department of Vertebrate Palaeontology. He was encouraged to explore drawing and modelling with modelling clay and caught the attention of the museum’s director, Henry Fairfield Osborn, who took Christman under his wing, encouraging him and supervising much of his work, and as the boy’s artwork developed, he attended New York’s Art Students League and the National Academy of Design, training that helped to refine and develop his artistic skills.

In 1900, a fifteen-year-old boy joined the staff of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Erwin S Christman had a passionate love of animals and was put to work making illustrations of fossil mammal skulls in the Department of Vertebrate Palaeontology. He was encouraged to explore drawing and modelling with modelling clay and caught the attention of the museum’s director, Henry Fairfield Osborn, who took Christman under his wing, encouraging him and supervising much of his work, and as the boy’s artwork developed, he attended New York’s Art Students League and the National Academy of Design, training that helped to refine and develop his artistic skills.

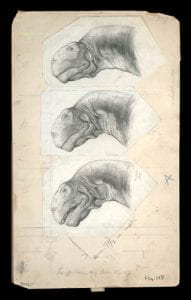

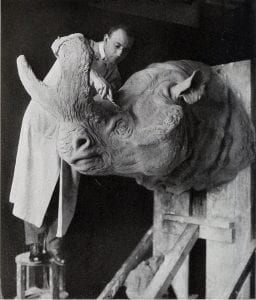

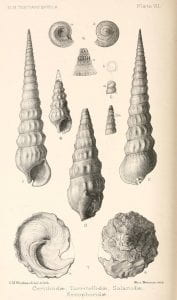

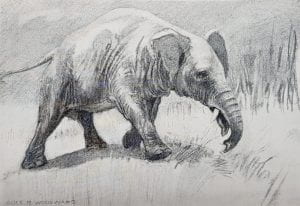

His drawings were initially in ink and wash and later he worked mostly in pen line but he also developed a skill in modelling and three-dimensional work; he worked alongside scientists at the museum as they tried to understand how prehistoric animals could be reconstructed.

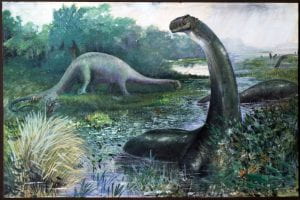

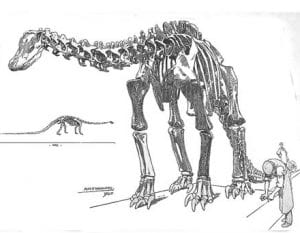

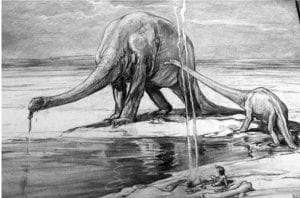

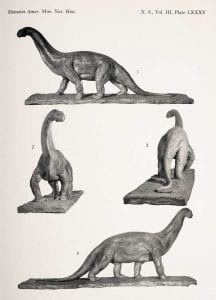

When Osborn and Charles Craig Mook published their “Characters and Restoration of the Sauropod Genus Camarasaurus Cope” in 1919, Christman created the restoration, a model working under the direction of William Gregory at the museum, and a series of drawings of the head of Camarasaurus as a full page plate. Christman also worked on life-size restorations, his skill in sculpture thriving under the encouragement and support of the museum staff.

Christman was ten years younger than Knight, who was working at the museum when Christman was there so it seems very unlikely that they wouldn’t have known and interacted with each other. Those of you familiar with Knight’s drawing will see that Christman’s style is more formal and precise than Knight’s slightly looser style, but the Camarasaurus head has the strong sense of form and engagement with the animal seen in Knight’s work.

So why isn’t Christman as well-known as Knight?

The answer is that, tragically, Christman died suddenly in 1921 of appendicitis, aged only thirty-six, leaving a wife and small children.

Wlliam Gregory, Christman’s collaborator at the museum, wrote a moving obituary in which it’s clear that Christman was popular, well-liked and very highly regarded at the museum. His loss to the museum was as great as his loss to palaeoart in general.

Images from AMNH Digital Archives

References

Gregory, William K . “Erwin S. Christman, 1885 – 1921: Draughtsman, Artist, Sculptor.” Natural History XX1, no. 6 (Nov-Dec) (1921): 620–25.

Osborn, Henry Fairfield, and Charles Craig Mook. “Characters and Restoration of the Sauropod Genus Camarasaurus Cope . From Type Material in the Cope Collection in the American Museum of Natural History.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 58, no. 6 (1919): 386–96.

Hoagland, Clayton. “They Gave Life to Bones.” The Scientific Monthly 56, no. 2 (1943): 114–33.