The city of Bristol, in the UK, has its own dinosaur! Thecodontosaurus antiquus was a small, herbivorous dinosaur of the late Triassic period, living in what is now the Bristol area around 230 million years ago.

The city of Bristol, in the UK, has its own dinosaur! Thecodontosaurus antiquus was a small, herbivorous dinosaur of the late Triassic period, living in what is now the Bristol area around 230 million years ago.

This part of the south west of England is formed of limestone, and when ‘Theco’ lived here, the climate was warm and wet, a bit like the Caribbean today. Creatures that died might be washed into rivers and into caves where they were fossilised.

In 1834, two eminent Bristolians, Henry Riley, a surgeon, and Samuel Stuchbury, the curator of the Bristol Institution, were looking for fossils in the limestone quarry in Durdham Down, which today forms part of Bristol’s ‘Downs’, a large, open, green public space.

They found the fossilised bones of a small prehistoric reptile, which they named in 1836, but bear in mind that it wasn’t until 1842 that Richard Owen recognised that prehistoric creatures being excavated and studied around the country represented a type of animal he named ‘dinosaurs’.

The name Thecodontosaurus means ‘ancient socket-toothed reptile (or lizard)’ which refers to the way its teeth sit in sockets in the jawbone (like ours) rather than being fused with the bone, as in most lizards. Riley and Stuchbury knew it was prehistoric but it wasn’t recognised as a dinosaur until around 1843. Theco is about the size of a Labrador dog.

Its fossilised bones were held in Bristol Museum but Bristol suffered a severe bombardment in the Blitz of World War II and the museum took a direct hit, yet many of the bones were salvaged and later some more fossils were found at Tytherington, near Bristol.

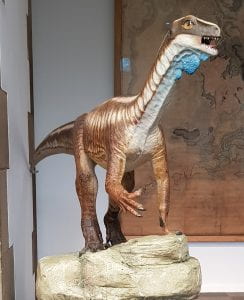

Theco became something of a local celebrity when it represented a new public engagement with science project run by the University of Bristol in 2000. With funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and others, from 2010 the University of Bristol’s Bristol Dinosaur Project involved students in a major outreach to local schools, targeting children in 7 – 9 and 14 – 15 age groups. The project also funded new research facilities at the University to process more fossils and employed local palaeoartist Bob Nicholls to sculpt a life-size model of Theco, working with scientists to make the model as accurate as possible.

The Bristol Dinosaur Project is still going strong, visiting schools in the area and engaging tomorrow’s palaeontologists. The model of Theco – also shown in the header – now resides in the Wills Memorial Building in Bristol.

The Bristol Dinosaur Project is still going strong, visiting schools in the area and engaging tomorrow’s palaeontologists. The model of Theco – also shown in the header – now resides in the Wills Memorial Building in Bristol.

References and further information: