Post by ANNA GRAYSON

I was delighted to find my photograph Still Life with Fossil Seafood accepted for the Royal Academy “Summer” Exhibition this year. They say “summer” but it has only just opened to the public and goes on until 2 January. So, maybe more of a Devensian or Anglian summer, but with shorter days. However, when you go into the show it has the colour and energy of the brightest summer. It is also available to view online here.

I was delighted to find my photograph Still Life with Fossil Seafood accepted for the Royal Academy “Summer” Exhibition this year. They say “summer” but it has only just opened to the public and goes on until 2 January. So, maybe more of a Devensian or Anglian summer, but with shorter days. However, when you go into the show it has the colour and energy of the brightest summer. It is also available to view online here.

I am a geologist by training (St Andrews) but couldn’t get a job in geology in those days because of my gender. My careers advisory officer advised me to apply to the BBC, which I did and much of the rest is history. After working variously as a studio manager, producer, reporter, general presenter etc, I eventually melded my two halves and started writing and presenting programmes about geology and writing a few short books and newspaper features. In my spare time and on holidays I collected fossils and minerals with my husband, Des Maxwell Clark.

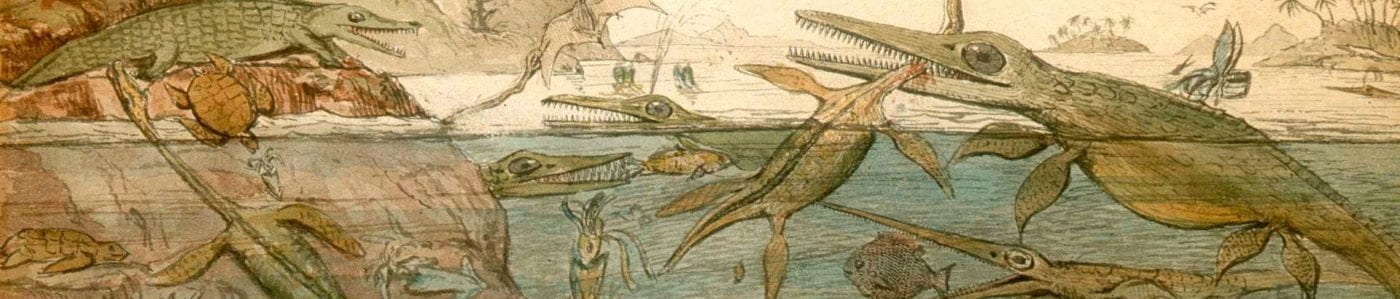

I think I will have to admit that it was the aesthetic quality of fossil and mineral specimens that had drawn me into the subject in the first place. The shape and form of some of the things we study are outstandingly beautiful, and the stories they can tell breathtaking and often epic. I would argue that as well as being scientifically important the specimens of our trade are like natural pieces of art, and not just any old art but the highest quality art.

Very occasionally my Mother accompanied us on fossil collecting trips and although she enjoyed the shape of ammonites, she was always hankering for lunch and would ask if they would have been good to eat when they were living. This rather charming thought has not left me. Yes, they may well have been utterly delicious.

A film I presented for the BBC’s Natural World series was named Postcards from the Past by my producer (Roger Jones) – the concept that fossils are like postcards from journeys of continental drift taken through earth history. If you know how to read them they will unfold great adventures and maybe some warnings about the extremes of climate that are possible on our planet. During the making of this film, specimens became the key way to engage the public with our science, alongside reconstructing environments of the past using archive film. (I called it operation Lyell in reverse!)

After taking early retirement I turned to fine art and became known for my photographic art, re-imagining famous works of art as photographs, using careful framing to add to the illusion of an updated oil painting. (See my website for more examples.) I had made well over 40 of these and already had three hung at the RA. But after visiting some particuarly gorgeous still life paintings in the Rijksmuseum and the Wallace Collection in London, I felt the traditional still life was a genre I could not ignore. The concept of fossils as food and geology as a series of aesthetic objects suddenly clicked in my brain with the need to shoot a still life, and so I started choosing pieces from our own collection and arranging them on the kitchen table on a small Dutch table carpet I had inherited from my Belgian Aunt.

I tried a variety of ammonites, but it was soon clear that strong ribbing and serpentine coiling was going to work best, so involute samples went back in the cabinet pretty quickly. All the best still life paintings have a lobster, and it just so happens that about 45 years ago my husband found a fine specimen of Meyeria magna on the Isle of Wight (I believe this beast has undergone a name change) so that had pride of place. I had to have another arthropod so my prize trilobite (pet name Nelson) went in the front. I needed some grapes, so used some carnelian and soapstone ones I’d bought in a charity shop, plus a rather fine piece of haematite from Florence Mine in Cumbria. A glistening cut lemon is often featured, and for that I substituted two slices of polished Scottish agate. Instead of silver vessels I used geodes from Morocco and a cluster of quartz xtals from Cornwall. Oysters – we need oysters, so Gryphaea was the obvious one to use there. (Hmm, I hate raw oysters, but love them cooked, I bet Gryphaea would have been nice prised out of his shell with a very strong oyster knife, wrapped in parma ham and fried!! Yummy.)

Orginally I’d planned to shoot the whole thing in candle light having previously shot an homage to Mary Anning that way. But it didn’t seem quite right this time. So the following morning I got up bright and early to find the eastern sun shining beautifully on my set. I made a few fine adjustments, put a reflector in and pressed the shutter. That was it. Job done.

Of course the hidden message in the traditional Dutch Still Life genre is the memento mori – that reminder of the fate that awaits us all, that we’re all gonna die… In my still life I have gone further, as firstly you can’t get more dead than a fossil and secondly the image is in fact a memento mori for the whole planet – there are at least two mass extinction events represented in there and, well everyone, another mass extinction does appear to be a fate that awaits as all. Think on it, I am telling my audience.

The reaction to the image has outstripped my expectations. Comments and enthusiasm from people that saw the image in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter made me feel this was the one I should choose for my RA application this year. I was right. It has gone down very well indeed. The framed image sold at one of the early private views, nearly a week before it opened to the public and orders for unframed prints (£120) are streaming in.

The show is on until 2 January, but to visit physically you have to book a slot in advance. It is well worth going. Look out for some other interesting artists such as Bristol-based Emma Stibbon RA who is interested in rapid geological change and active landforms. Her multi-layered prints are a science in themselves and very beautiful. Geology and art are natural soulmates.