(With thanks to those who have suggested sources or sent information about these films.)

I have already written about the first drawn animated dinosaur, Gertie the Dinosaurus, here, but dinosaurs were also animated using stop-frame animation during the early 20th century. This is a survey of the very first stopframe animations of dinosaurs, covering the period from 1914 to 1923. It is worth mentioning that cinema as an art form for less than two decades, and the potential for special effects became very obvious very quickly.

I have already written about the first drawn animated dinosaur, Gertie the Dinosaurus, here, but dinosaurs were also animated using stop-frame animation during the early 20th century. This is a survey of the very first stopframe animations of dinosaurs, covering the period from 1914 to 1923. It is worth mentioning that cinema as an art form for less than two decades, and the potential for special effects became very obvious very quickly.

There was an animation of dinosaurs that were possibly made by stopframe in 1905, based on the comic strip “Prehistoric Peeps”, that ran in the British satire magazine, Punch. A version of it has been digitised and is held by the British Film Institute but is unavailable for viewing. (If it does become available, I will update the post.)

So Gertie the Dinosaurus was Winsor McCay’s vaudeville act that opened in February 1914, and in December 1914 a film was released of the animated cartoon embedded in a live-action story (made because McCay’s employer objected to him spending so much time on his vaudeville act). During 1914, a film was also released directed by D. W. Griffiths (1875-1948) entitled Brute Force (also known as The Primitive Man) in which people at a sophisticated cocktail party are transported back in time to become cave men. In one scene, here, a dinosaur is seen in the background, which does not move very much, just its jaw opening and closing, and it is likely to be a full-size model.

the animated cartoon embedded in a live-action story (made because McCay’s employer objected to him spending so much time on his vaudeville act). During 1914, a film was also released directed by D. W. Griffiths (1875-1948) entitled Brute Force (also known as The Primitive Man) in which people at a sophisticated cocktail party are transported back in time to become cave men. In one scene, here, a dinosaur is seen in the background, which does not move very much, just its jaw opening and closing, and it is likely to be a full-size model.

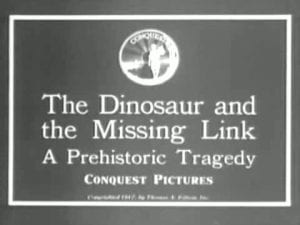

The theme of cavemen co-existing with dinosaurs ran through several early animations, the next being a 6-minute film by the animation pioneer Willis O’Brien. It was made by O’Brien in 1915 on a budget of $5,000 – he had made a 90 second test reel of a dinosaur and a caveman while working as assistant to the head architect of the 1915 San Francisco World Fair and some of his models and the test piece were seen by one of the exhibitors, Herman Wobber. Wobber then commissioned The Dinosaur and the Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy, which was seen by Thomas Edison and released by Edison’s distribution company Conquest Pictures in 1917.

The theme of cavemen co-existing with dinosaurs ran through several early animations, the next being a 6-minute film by the animation pioneer Willis O’Brien. It was made by O’Brien in 1915 on a budget of $5,000 – he had made a 90 second test reel of a dinosaur and a caveman while working as assistant to the head architect of the 1915 San Francisco World Fair and some of his models and the test piece were seen by one of the exhibitors, Herman Wobber. Wobber then commissioned The Dinosaur and the Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy, which was seen by Thomas Edison and released by Edison’s distribution company Conquest Pictures in 1917.

The plot is one that keeps appearing in caveman films, namely love triangles. In this film, two suitors, the Duke and Stonejaw Steve are rivals for the hand of Araminta Rockface who lives in a cave with her father. O’Brien creates some classic slapstick humour, with the Duke bumping into a tree and when the two fight, Stonejaw drops the Duke into the cooking cauldron outside the cave. An intertitle then tells us that a third suitor, our hero Theophilus Ivory-head has arrived, so Araminta invites all three of them into their home for tea (which the intertitle tells us has not been discovered yet!). While the three of them argue inside the cave, their hated enemy, Wild Willie, the “missing link” steals their food from the cauldron and makes off with it. When Araminta’s father sees that the food has gone, he sends the rivals out to get dinner, Duke and Stonejaw to get meat, and Theophilus to get fish. The meat-hunters come across a “desert quail” and in another piece of slapstick, Stonejaw fires an arrow at the bird which misses and embeds itself in the Duke’s backside, who falls head first into the cauldron. Meanwhile, Theophilus has reached the lake where a dinosaur has come to the water to drink; Wild Willie has also decided to visit the lake to find some snakes to eat, mistakes the dinosaur’s tail for a snake and Wild Willie and the dinosaur get into a fight. The dinosaur kills Wild Willie and leaves, and Theophilus decides to claim the victory over Wild Willie for himself. When the others arrive, he is hailed as a hero and wins the hand of Araminta.

and Stonejaw Steve are rivals for the hand of Araminta Rockface who lives in a cave with her father. O’Brien creates some classic slapstick humour, with the Duke bumping into a tree and when the two fight, Stonejaw drops the Duke into the cooking cauldron outside the cave. An intertitle then tells us that a third suitor, our hero Theophilus Ivory-head has arrived, so Araminta invites all three of them into their home for tea (which the intertitle tells us has not been discovered yet!). While the three of them argue inside the cave, their hated enemy, Wild Willie, the “missing link” steals their food from the cauldron and makes off with it. When Araminta’s father sees that the food has gone, he sends the rivals out to get dinner, Duke and Stonejaw to get meat, and Theophilus to get fish. The meat-hunters come across a “desert quail” and in another piece of slapstick, Stonejaw fires an arrow at the bird which misses and embeds itself in the Duke’s backside, who falls head first into the cauldron. Meanwhile, Theophilus has reached the lake where a dinosaur has come to the water to drink; Wild Willie has also decided to visit the lake to find some snakes to eat, mistakes the dinosaur’s tail for a snake and Wild Willie and the dinosaur get into a fight. The dinosaur kills Wild Willie and leaves, and Theophilus decides to claim the victory over Wild Willie for himself. When the others arrive, he is hailed as a hero and wins the hand of Araminta.

The dinosaur bears a strong resemblance to Gertie, and Wild Willie to O’Brien’s later creation King Kong, both characters based on the gorilla which at the time had a very negative reputation for fierceness. Edison was so impressed by the film he employed O’Brien to make films for Conquest Pictures, and O’Brien made several shorts.

One of these shorts was R.F.D. 10,000 B.C., made in 1917. (“R.F.D.” refers to the Rural Free Delivery system in early 20th century America whereby mail would be delivered to outlying isolated communities such as farms.) The story centres around the mailman, who can be seen in this clip delivering the mail on a cart – the cart has round stone wheels and is pulled along by a dinosaur in a harness. Again, the dinosaur is very similar to Gertie, but the harness and cart are rather prescient of the Hanna-Barbera 1960s cartoon The Flintstones.

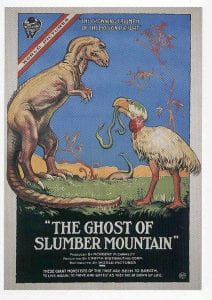

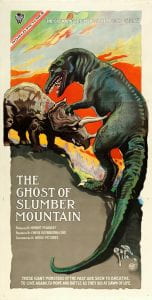

One of O’Brien’s more well-known films was released in 1918, The Ghost of Slumber Mountain, in which O’Brien worked with Obrien worked with Herbert Dawley, and both appear in the film. It was a much more ambitious project, that originally ran at three reels around 40 minutes, but when it was shown at the Strand Theater, the manager ordered it to be shortened. It was eventually cut to 12 mins, but more material that was thought to be lost has been found taking the length to 19 mins. A reference on the Wikipedia entry claims that Barnum Brown was an advisor on the film and O’Brien based the dinosaurs on Knight’s paintings.

One of O’Brien’s more well-known films was released in 1918, The Ghost of Slumber Mountain, in which O’Brien worked with Obrien worked with Herbert Dawley, and both appear in the film. It was a much more ambitious project, that originally ran at three reels around 40 minutes, but when it was shown at the Strand Theater, the manager ordered it to be shortened. It was eventually cut to 12 mins, but more material that was thought to be lost has been found taking the length to 19 mins. A reference on the Wikipedia entry claims that Barnum Brown was an advisor on the film and O’Brien based the dinosaurs on Knight’s paintings.

The story is based around Uncle Jack (played by Dawley) telling his nephews an adventure story – he and his friend had visited Slumber Mountain in the Valley of Dreams. Jack and friend find a deserted cabin belonging to dead Mad Dick who had a magic telescope. Jack goes to the cabin where the ghost of Mad Dick (played by O’Brien) tells him to look through the telescope, and Jack sees back into the Cretaceous; he sees a Brontosaurus, a strange wingless bird (that looks very similar to the “desert quail” from The Dinosaur and the Missing Link) and two Triceratops fighting. A T. rex then attacks and starts to eat one of the Triceratops, a shot strangely prescient of the T. rex eating the Stegosaurus in Disney’s Fantasia. Jack is chased by the T. rex but then wakes up, he had fallen asleep by the campfire and it was all a dream, and his nephews are pleased with such a fine adventure story. The clip of the dinosaurs can be seen here.

The story is based around Uncle Jack (played by Dawley) telling his nephews an adventure story – he and his friend had visited Slumber Mountain in the Valley of Dreams. Jack and friend find a deserted cabin belonging to dead Mad Dick who had a magic telescope. Jack goes to the cabin where the ghost of Mad Dick (played by O’Brien) tells him to look through the telescope, and Jack sees back into the Cretaceous; he sees a Brontosaurus, a strange wingless bird (that looks very similar to the “desert quail” from The Dinosaur and the Missing Link) and two Triceratops fighting. A T. rex then attacks and starts to eat one of the Triceratops, a shot strangely prescient of the T. rex eating the Stegosaurus in Disney’s Fantasia. Jack is chased by the T. rex but then wakes up, he had fallen asleep by the campfire and it was all a dream, and his nephews are pleased with such a fine adventure story. The clip of the dinosaurs can be seen here.

The collaboration between Dawley and O’Brien was not a happy one, and it has been said that Dawley re-used some of the discarded footage to make his next film, Along the Moonbeam Trail.[1] However, the IMDb entry states that this was not the case, and an examination of the two films shows the difference between the animation style and quality in the films.[2]

This film was released in 1920 and seems to be made by Dawley himself. The version I’ve seen runs at about 14 mins and a splendidly restored version can be seen here. Dawley again features in the film with a familiar

This film was released in 1920 and seems to be made by Dawley himself. The version I’ve seen runs at about 14 mins and a splendidly restored version can be seen here. Dawley again features in the film with a familiar starting story of Uncle Jack and his nephews, this time, with a slightly more complicated story. While they are camping, Jack tells of the fairy of dreams, Queen Mab, who appears in their dreams as a scantily clad, fetching young lady, who offers them a wish; they ask for a magic airplane that will take them to the moon. The airplane duly appears and as they leave, she gives them a magic ring to rub if they need her help. They take off and fly out into space, passing “Mars”, deposed to a humble traffic cop of the skies, and the Man in the Moon among other characters, and to escape a pursuing pterodactyl they land on a strange planet. They hide in a cave from “frightful monsters”, this clip showing that they see a Stegosaurus (a lizard with plates glued on?), a “Trachodon” and the inevitable T. rex which tries to reach them inside their cave. When it fails, it fights the Trachodon, and we see Jack and the nephews, the boys crying at this fearsome scene. Queen Mab reappears and although the finale is missing, an intertitle explains that the crying boy had rubbed the magic ring and he wishes them safely home.

starting story of Uncle Jack and his nephews, this time, with a slightly more complicated story. While they are camping, Jack tells of the fairy of dreams, Queen Mab, who appears in their dreams as a scantily clad, fetching young lady, who offers them a wish; they ask for a magic airplane that will take them to the moon. The airplane duly appears and as they leave, she gives them a magic ring to rub if they need her help. They take off and fly out into space, passing “Mars”, deposed to a humble traffic cop of the skies, and the Man in the Moon among other characters, and to escape a pursuing pterodactyl they land on a strange planet. They hide in a cave from “frightful monsters”, this clip showing that they see a Stegosaurus (a lizard with plates glued on?), a “Trachodon” and the inevitable T. rex which tries to reach them inside their cave. When it fails, it fights the Trachodon, and we see Jack and the nephews, the boys crying at this fearsome scene. Queen Mab reappears and although the finale is missing, an intertitle explains that the crying boy had rubbed the magic ring and he wishes them safely home.

The film is interesting because it was one of the first to show actors and dinosaurs (and Queen Mab!) in the same shot, and as much of the animation dinosaur action is seen from inside the cave, it can be framed by a dark masque, reducing the required resolution of the images.[3]

The last film I want to consider here is Buster Keaton’s 1923 film Three Ages. Buster was born and bred into vaudeville, his

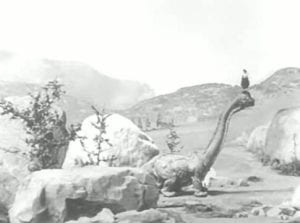

The last film I want to consider here is Buster Keaton’s 1923 film Three Ages. Buster was born and bred into vaudeville, his family travelling the vaudeville circuits with Buster performing on stage with his parents from a very young age. The film was made in three sections, each telling much the same love story; the sections are The Stone Age, The Roman Age and the Modern Age. It was made in this format in case it bombed, in which case it could be easily separated into three discrete films. In the first section, The Stone Age, Buster is a caveman, and makes his entrance riding the back of a dinosaur, here. This was inspired by his seeing Gertie the Dinosaur, probably as the vaudeville act, but when he came to make Three Ages, he was insistent that he would ride into the scene on a dinosaur like Gertie.[4] His rival in love, played by Wallace Beery who would go on to play Challenger in the 1925 Lost World, rides into the scene on an elephant with strange-looking tusks that is supposed to be a mammoth.

family travelling the vaudeville circuits with Buster performing on stage with his parents from a very young age. The film was made in three sections, each telling much the same love story; the sections are The Stone Age, The Roman Age and the Modern Age. It was made in this format in case it bombed, in which case it could be easily separated into three discrete films. In the first section, The Stone Age, Buster is a caveman, and makes his entrance riding the back of a dinosaur, here. This was inspired by his seeing Gertie the Dinosaur, probably as the vaudeville act, but when he came to make Three Ages, he was insistent that he would ride into the scene on a dinosaur like Gertie.[4] His rival in love, played by Wallace Beery who would go on to play Challenger in the 1925 Lost World, rides into the scene on an elephant with strange-looking tusks that is supposed to be a mammoth.

This is by no means definitive, and there are other, less well-known stopframe animations that I will consider in The First Dinosaurs (Part Two) but this blog has partly come out of an online discussion with some of the Palaeomedia Project members. Please do let me know if you have suggestions or corrections!

[1] Donald F. Glut, The Dinosaur Scrapbook (Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1980). p. 83

[2] With thanks to the Palaeomedia group discussion that looked at these animations.

[3] Thanks to Dan Hedger for suggesting this, and for also pointing out that with stop frame, the models have to have “fixed” feet to support them, so always seem to shuffle.

[4] Donald Crafton, “McCay and Keaton: Colligating, Conjecturing, and Conjuring,” Film History: An International Journal 25, no. 1–2 (2013): 31–44, https://doi.org/10.1353/fih.2013.0018.