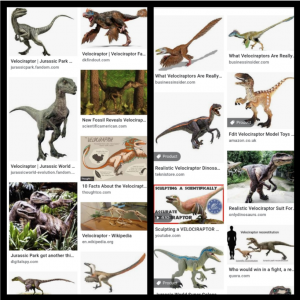

Last time, I was proposing that the Jurassic Park movieraptors could be viewed as sci fi cousins of the fantastical serpent-dragon. But out of all the dragons, the movieraptor bears the greatest physical similarity to the cockatrice, with the wyvern as a distant second. And since I have already mentioned Dilophosaurus, whose persistence could too be explained by reference to enchanting story tropes, I want to zoom out and explore the link between select Dinosaur Renaissance-style theropods of Jurassic Park and the cockatrice/basilisk in particular.

But before we can proceed, I need to mention that I have made some amendments to the definition of the movieraptor.

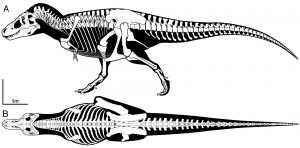

Carnosauriform: a carnivorous, bipedal dinosaur or dinosaur-like reptile rendered in the Dinosaur Renaissance style; scaly (entirely or largely), lean, usually shrink-wrapped in certain areas of its anatomy, and with hands, whose neutral position is pronated (downward-facing).

Movieraptor/Videoraptor: a carnosauriform with sickle claws on its feet and which can be classified as a member of the non-avialan Paraves. Usually, it hunts in packs.

This is because I had realized that the Jurassic Park Troodon (more on it in Part 2) essentially fits the description of the movieraptor as a scaly sickle-clawed dinosaur despite not being a dromaeosaurid.

Due to how bird-like paravians we are discovering them to be, and the real possibility of at least some of them being secondarily flightless, some ornithologists (e.g., Feduccia, 2013) and at least one palaeontologist (Gregory Paul, 2002) opted to call them outright birds. Perhaps Paraves, or even Pennaraptora (Paraves + Oviraptorosauria), might become a synonym of Aves (unless one is committed to a crown-group definition), so the movieraptor definition might be reformulated as a non-avialan, sickle-clawed bird rendered as a carnosauriform.

Now, let us know the basilisk a bit more. The earliest type, first described by Pliny the Elder (based on some actual small but most venomous snake of Nicander, 2nd century BC) as living in Cyrenaica (present-day Libya), has an unclear origin. One theory holds that is was based on the Egyptian cobra via stylized uraei of Ancient Egypt (Alexander, 1963). In that case, the basilisk’s white crown-like spot on the head may have come from sun disks on uraei and its killer gaze either from spitting venom or alleged powers of the uraei, which would have also have been the source of a poisonous breath (Alexander, 1963, pp. 171-173). This basilisk is enemies with and can be killed by the ichneumon, a weasel- or (rather) mongoose-like mammal. However, a novel hypothesis of Lenders and Janssen (2014) regards the basilisk as (based on) a grass snake, with the crown-like mark based on the species’ golden neck ring and its poison (whether in the gaze, smell, breath or hiss) being a Christian subversion of pagan beliefs tying the snake to land fertility; some medieval bestiaries link basilisks with agricultural dung heaps, where grass snakes lay their eggs (Lenders and Janssen, 2014). There is a discrepancy between the two views on how big Pliny’s basilisk was: four to six feet (Alexander, 1963) or only a foot long, too small to be even a hatchling cobra (Lenders and Janssen, 2014). Perhaps the king of serpents simply was dreamt of twice.

Whatever the origins of the first basilisk, a second emerged through illustrations of snakes with two wings and two legs, starting in the 10th century AD, and ending as a cock with a snaky tail by the 12th century (Alexander, 1963, pp. 175-176; Breiner, 1979, p. 30). This basilisk, sometimes described with a turkey’s neck and/or frog-like eyes, came to be known as the cockatrice, a French rendering of cocatris, one Latin variant for “crocodile”. How “cockatrice” came about has to do with the shifting meanings of the players of another story of Pliny, involving a crocodile having its belly eaten from the inside by another creature; this is a matter of bewildering confusion and I refer the reader to the work of Laurence A. Breiner (1979, pp. 30-36). Its rooster-like crest is due to the former basilisk’s mark being exaggerated by medieval writers (Alexander, 1963, p. 176).

Whatever the origins of the first basilisk, a second emerged through illustrations of snakes with two wings and two legs, starting in the 10th century AD, and ending as a cock with a snaky tail by the 12th century (Alexander, 1963, pp. 175-176; Breiner, 1979, p. 30). This basilisk, sometimes described with a turkey’s neck and/or frog-like eyes, came to be known as the cockatrice, a French rendering of cocatris, one Latin variant for “crocodile”. How “cockatrice” came about has to do with the shifting meanings of the players of another story of Pliny, involving a crocodile having its belly eaten from the inside by another creature; this is a matter of bewildering confusion and I refer the reader to the work of Laurence A. Breiner (1979, pp. 30-36). Its rooster-like crest is due to the former basilisk’s mark being exaggerated by medieval writers (Alexander, 1963, p. 176).

In the 16th century, the cockatrice-basilisk came to Poland and inspired the famous Warsaw legend. There, the cockatrice dwells in basements of the Krzywe Koło street and kills its victims by sight, meaning hardly anyone dares to descend underground or come out at night. Eventually, the death of at least one child provokes the people of Warsaw. They send a guy, sentenced earlier to death, clad in “armour” of mirrors to end the draconic monstrosity by making it glance at its own reflection. In one variant of the legend, the sentenced guy himself comes up with the shining armour (Sala, 2024, p. 77). In others, it is the idea of a brilliant scholar and the sentenced one simply volunteers (Oppman, 2008, Orłoń and Tyszkiewicz, 1988, pp. 100-102). In addition, either two unnamed children die (Orłoń and Tyszkiewicz, 1988, Sala, 2024) or a brother and sister are led to the basements by their mischievous friend, who is the one that died (the siblings managed to hide and survive) (Oppman, 2008).

As we trace the evolution of Dilophosaurus in Jurassic Park the book and the film (Spielberg, 1993), we can observe some remarkable parallels to the origins of the first basilisk. Michael Crichton initially invented the venomous spit to account for the notch in the upper jaw that apparently weakened its bite (discussed in Brown and Marsh, 2021). Later, concept artist and puppeteer Mark “Crash” McCreery incorporated the neck frill into the design of Dilophosaurus (Stan Winston School, 2013, 0:26-0:37), evidently inspired by the frilled lizard. Interestingly, the frill is vaguely like the hood of the cobra, plus it rattles, the sound taken directly from the rattlesnake (Jurassic World, 2024, 1:02). While a departure from reality, these qualities give the Dilophosaurus (a.k.a. the Spitter) a serpentine gloss, potentially ensuring its rapid rise to stardom, as was probably the case with dragons of old.

Even so, Dilophosaurus has a unique character compared to the basilisk/cockatrice; the latter is always seriously deadly. In contrast, the Dilophosaurus was initially curious of Denis Nedry, even playfully hiding behind a tree. In that, it resembles more the lonely Gollum as he first met Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit (Tolkien, 1998). Of course, this cuteness serves to make Nedry’s final demise even more dramatic, but had Nedry been more courteous an

d less selfish (and had some food to offer), he might have won over the creature and keep it as a guardian pet.

Like the movieraptor before, the basilisk Dilophosaurus has established itself in the wider media. And this image has ossified by the time Marsh and Rowe (2020) updated the knowledge base through a complete re-description. Most significantly, the notch in Dilophosaurs’s upper jaw was found to be far more robust than previously believed, permitting to hunt even large sauropodomorphs (p. 27 of the study) and destroying any rationale for venomous capacity. Let us hope that another visionary sees that Dilophosaurus need not the mystical powers of the uraeus; sheer size and raw strength are enough.

References

Alexander, R. M. (1963) ‘The Evolution of the Basilisk’, Greece and Rome, 10(2), pp. 170-181.

Breiner, L. A. (1979) ‘The Career of the Cockatrice’, Isis, 70(1), pp. 30-47.

Brown, M. A. and Marsh, A. D. (2021) ‘The Real Dilophosaurus Would Have Eaten the Jurassic Park Version for Breakfast’, Scientific American, (no. 19/01/2025).

Cate, B. t. 2011. In: natrix.jpg, O.r.-g.s.-N.n. (ed.). Wikimedia Commons.

Feduccia, A. (2013) ‘Bird Origins Anew’, The Auk, 130(1), pp. 1-12.

Ghorayr 2011. Ouraeus (Naja haje legionis) – Egyptian cobra. In: Ouraeus.png, E.C. (ed.). Wikimedia Commons.

GoShows 2012. Reverse Side of Tutankhamun’s Throne. In: Throne.jpg, G.U.C.T.s. (ed.). My Flicker.com.

Lenders, H. J. R. and Janssen, I. A. W. (2014) ‘The Grass Snake and the Basilisk: From Pre-Christian Protective House God to the Antichrist’, Environment and History, 20(3), pp. 319-346.

Marsh, A. D. and Rowe, T. B. (2020) ‘A Comprehensive Anatomical and Phylogenetic Evaluation of Dilophosaurus wetherilli (Dinosauria, Theropoda) with Descriptions of New Specimens from the Kayenta Formation of Northern Arizona’, Journal of Paleontology, 94(S78), pp. 1-103.

MorphinESTP 2022. Mandalay spitting cobra (Naja mandalayensis). In: 2.jpg, N.m.C.L. (ed.). Wikimedia Commons.

Oppman, A. (2008) ‘Bazyliszek’, in Włodarczyk, B. (ed.) Legendy polskie. Krakow: GREG, pp. 23-34.

Orłoń, M. and Tyszkiewicz, J. (1988) Legendy i podania polskie. 1st, reprint edn. Warsaw: PTTK “Kraj”.

Paul, G. S. (2002) Dinosaurs of the Air: The Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinosaurs and Birds. USA: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sala, B. G. (2024) Księga smoków polskich. 2nd, reprint edn. Poland: BoSz.

School, S. W. 2013. JURASSIC PARK’s Spitter – Building the Dilophosaurus Dinosaur puppet. YouTube.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (1998) The Hobbit, or There and Back Again. 5th edn. England: HarperCollins. Original publication in 1937.

Jurassic Park, 1993. Blu-Ray. Directed by Spielberg, S. United States: Universal Pictures.

World, J. 2024. Jurassic Park – Dinosaur Sounds with Gary Rydstrom. YouTube.

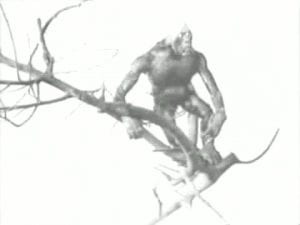

One of the most prevalent “what if” scenarios regarding prehistoric life, if not THE most prevalent, is the idea of how dinosaurs would have evolved if the massive asteroid never hit the Earth. Some are more grounded speculative evolution scenarios like the Speculative Dinosauria Project, while others are more “hard fantasy” worlds like Tales of Kaimere. However, one particular take on this “what if” comes in the form of the “Dinosauroid”. Created by Dale A. Russel in 1982, it depicts a Troodon/Stenonychosaurus as having evolved a very similar body shape to modern humans to occupy an identical niche. A steady increase in EQ, a very large braincase and eye sockets, and a language similar to bird songs were among its most notable traits. While an interesting and creative thought experiment, it’s been subjected to criticism from other paleontologists. Some accused it of over-anthropomorphization and misunderstanding of why humans developed their distinct body plans, with Darren Naish suggesting an “evolved” Troodontid would retain a more standard theropod plan. Such suggestions come into play with the real topic of this review. 25 years later, a children’s miniseries would be released with an alternate take on the “Dinosauroid” theory. Or in this case, “Dinosapien”. A series that is similarly charming and yet equally uncanny.

One of the most prevalent “what if” scenarios regarding prehistoric life, if not THE most prevalent, is the idea of how dinosaurs would have evolved if the massive asteroid never hit the Earth. Some are more grounded speculative evolution scenarios like the Speculative Dinosauria Project, while others are more “hard fantasy” worlds like Tales of Kaimere. However, one particular take on this “what if” comes in the form of the “Dinosauroid”. Created by Dale A. Russel in 1982, it depicts a Troodon/Stenonychosaurus as having evolved a very similar body shape to modern humans to occupy an identical niche. A steady increase in EQ, a very large braincase and eye sockets, and a language similar to bird songs were among its most notable traits. While an interesting and creative thought experiment, it’s been subjected to criticism from other paleontologists. Some accused it of over-anthropomorphization and misunderstanding of why humans developed their distinct body plans, with Darren Naish suggesting an “evolved” Troodontid would retain a more standard theropod plan. Such suggestions come into play with the real topic of this review. 25 years later, a children’s miniseries would be released with an alternate take on the “Dinosauroid” theory. Or in this case, “Dinosapien”. A series that is similarly charming and yet equally uncanny. I was delighted to find my photograph Still Life with Fossil Seafood accepted for the Royal Academy “Summer” Exhibition this year. They say “summer” but it has only just opened to the public and goes on until 2 January. So, maybe more of a Devensian or Anglian summer, but with shorter days. However, when you go into the show it has the colour and energy of the brightest summer. It is also available to view online

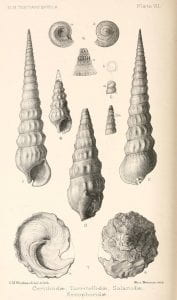

I was delighted to find my photograph Still Life with Fossil Seafood accepted for the Royal Academy “Summer” Exhibition this year. They say “summer” but it has only just opened to the public and goes on until 2 January. So, maybe more of a Devensian or Anglian summer, but with shorter days. However, when you go into the show it has the colour and energy of the brightest summer. It is also available to view online

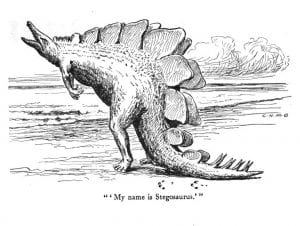

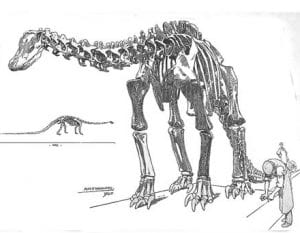

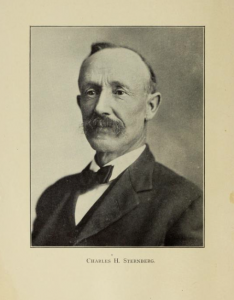

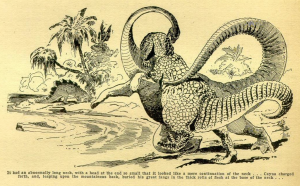

Sternberg’s prose is colorful. He paints vivid pictures that, although dated by today’s science, are evocative of a lost era. Here he describes the battle between a Trachodon and a Gorgosaurus:

Sternberg’s prose is colorful. He paints vivid pictures that, although dated by today’s science, are evocative of a lost era. Here he describes the battle between a Trachodon and a Gorgosaurus:

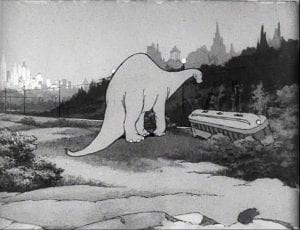

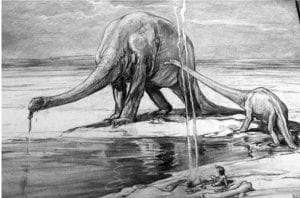

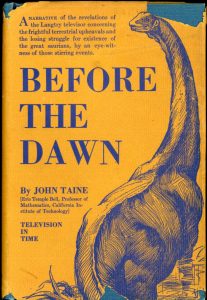

1934’s Before the Dawn by John Taine (pen name of Eric Temple Bell) is perhaps the first novel featuring dinosaur protagonists, predating Bakker’s novel by sixty-one years. The book’s prehistoric scenes are framed by scientists watching the beasts through some kind of time screen. One of the men has devised a means of replaying a residue of light within crystals just as someone might play grooves left by sound on an LP. The pseudoscience is beside the point, it’s just a vehicle to get to the dinosaurs.

1934’s Before the Dawn by John Taine (pen name of Eric Temple Bell) is perhaps the first novel featuring dinosaur protagonists, predating Bakker’s novel by sixty-one years. The book’s prehistoric scenes are framed by scientists watching the beasts through some kind of time screen. One of the men has devised a means of replaying a residue of light within crystals just as someone might play grooves left by sound on an LP. The pseudoscience is beside the point, it’s just a vehicle to get to the dinosaurs.