NEW GUEST POST FROM ERIC AMES. JR

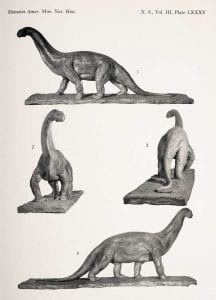

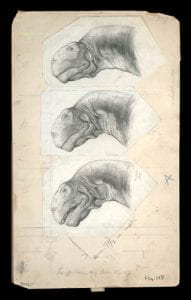

One of the most prevalent “what if” scenarios regarding prehistoric life, if not THE most prevalent, is the idea of how dinosaurs would have evolved if the massive asteroid never hit the Earth. Some are more grounded speculative evolution scenarios like the Speculative Dinosauria Project, while others are more “hard fantasy” worlds like Tales of Kaimere. However, one particular take on this “what if” comes in the form of the “Dinosauroid”. Created by Dale A. Russel in 1982, it depicts a Troodon/Stenonychosaurus as having evolved a very similar body shape to modern humans to occupy an identical niche. A steady increase in EQ, a very large braincase and eye sockets, and a language similar to bird songs were among its most notable traits. While an interesting and creative thought experiment, it’s been subjected to criticism from other paleontologists. Some accused it of over-anthropomorphization and misunderstanding of why humans developed their distinct body plans, with Darren Naish suggesting an “evolved” Troodontid would retain a more standard theropod plan. Such suggestions come into play with the real topic of this review. 25 years later, a children’s miniseries would be released with an alternate take on the “Dinosauroid” theory. Or in this case, “Dinosapien”. A series that is similarly charming and yet equally uncanny.

One of the most prevalent “what if” scenarios regarding prehistoric life, if not THE most prevalent, is the idea of how dinosaurs would have evolved if the massive asteroid never hit the Earth. Some are more grounded speculative evolution scenarios like the Speculative Dinosauria Project, while others are more “hard fantasy” worlds like Tales of Kaimere. However, one particular take on this “what if” comes in the form of the “Dinosauroid”. Created by Dale A. Russel in 1982, it depicts a Troodon/Stenonychosaurus as having evolved a very similar body shape to modern humans to occupy an identical niche. A steady increase in EQ, a very large braincase and eye sockets, and a language similar to bird songs were among its most notable traits. While an interesting and creative thought experiment, it’s been subjected to criticism from other paleontologists. Some accused it of over-anthropomorphization and misunderstanding of why humans developed their distinct body plans, with Darren Naish suggesting an “evolved” Troodontid would retain a more standard theropod plan. Such suggestions come into play with the real topic of this review. 25 years later, a children’s miniseries would be released with an alternate take on the “Dinosauroid” theory. Or in this case, “Dinosapien”. A series that is similarly charming and yet equally uncanny.

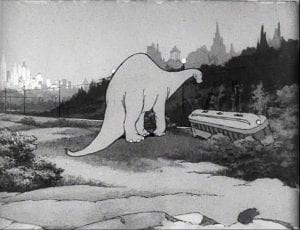

Released in 2007 by BBC Worldwide and CCI Entertainment, Dinosapien was presented in Canada through BBC Kids, the UK through the CBBC Channel, and in the United States through Discovery Kids (Where I was introduced to it.) The premise of the series is that dinosaurs had survived and existed in an underground world, but a trio of them had emerged from their realm after an earthquake: A teenage evolved Dromaeosaurus named Eno, and an opposing pair of evolved ornithichians (A cross between Prenocephale and Pinacosaurus) known as “The Diggers”. During a dinosaur-themed summer camp in Canada, one of the camp counselors Lauren encounters Eno and develops a friendship with him. It’s up to Lauren to help Eno get back home and figure out the cause of her father’s disappearance.

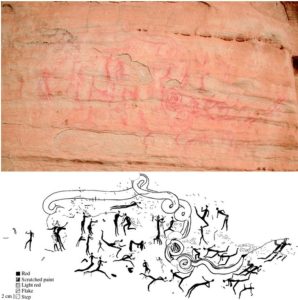

Along with the typical “find a missing parent” and “bring a lost animal back home” tropes, Dinosapien has a surprisingly amount of plot for a 15-episode kid’s show, a lot of which is pretty silly. There’s stuff like the “Dinosapien Theory”, which basically tells of intelligent dinosaurs that once coexisted with and were hunted by Native Americans, and how Lauren’s father was searching for evidence of them in the Badlands before he disappeared. There’s also a prophecy about the Thunderbird coming to defend the land from the Dinosapiens, which has a very… strange ending, shall we say? And of course, there’s the subplot of Dr. Aikens, the main villain of the show, slowly realizing the reality of such a theory and making an effort to destroy the Dinosapiens. Again, a lot of this show’s plot is incredibly silly and a bit overdramatic at times, but it’s still very entertaining.

Moving onto characters, Dinosapien has a reasonably sized cast of varying levels of quality. The main character Lauren (Brittney Wilson) is a decent enough protagonist with a likeable

personality and a sense of agency in the plot. Her friendship with Eno is believable enough and she does a good job acting as if the CGI dinosaurs are really there. Her best friend Courtney (MacKenzie Porter) is little more than a valley girl stereotype but provides a couple good laughs and feels like a legit best friend to Lauren. Kit (Bronson Pelletier) is likeable but doesn’t have much of a personality outside of the general “good guy” archetype, but his relationship with his uncle is admittedly interesting. Chris (Jeffrey Watson) can come across as a bit boring, with his only real personality trait being “lead counselor”. The twin kid characters Nelson (Brendan Meyer) and Danny (Alexandra Gingras) fare a bit worse. As with a lot of kid characters in paleomedia, they can come across as annoying know-it-alls, especially in the first few episodes. However, their little subplot later in the series invertedly helping Dr. Aikens with his “research” does improve them a bit. Conversely, the British and Native characters are the cast’s highlights. Lauren’s mother, Dr. Hilary Slayton (Suzanna Hamilton) provides a surprisingly earnest performance for a show of this caliber. Rather than just a stereotypical “aloof mother”, she really comes across as likeable and intelligent while also being a grieving “widow”. The mysterious character Ten Bears (Dean Manywounds) is similar. This mysterious character has a special interest in these Dinosapiens and despite the utter silliness of the plot, he performs it with utmost sincerity to the point that you can’t help but get invested. Especially whenever he interacts with the Diggers. Finally, Dr. Aikens (James Coombes) is the best character in the show. He embraces the full-on absurdity of the plot and plays his role as someone who wants to destroy the Dinosapiens lest they destroy humanity in such an overdramatic, goofy way that it becomes incredibly entertaining. It almost feels like he’s having flashbacks of being attacked on Isla Sorna in The Lost World, the way he talks about extinct dinosaurs and these Dinosapiens.

Speaking of Dinosapiens, let’s talk about them a bit. Suffice to say, these “evolved” dinosaurs look a tad… uncanny. Especially Eno. His human hair-like feathering on his head, hunch back, and flat face combined with the otherwise typical theropod body plan makes for a very weird design, not to mention the very human expressions he tends to make. The Diggers (named Green Eyes and Cerepta by Lauren) fare a little better design-wise, but they’re still fairly disproportionate. The Prenocephale and Pinacosaurus elements don’t really mesh well together and seeing such a heavily armored body supported by such thin, lanky legs is pretty silly. However, while the designs are a mixed bag, the way they explore the idea of “intelligent dinosaurs” is admittedly interesting. Eno’s friendship with Lauren is legitimately heartwarming and is properly developed, and while him talking like a parrot is a little weird, it makes sense given the show’s concept. Both he and the Diggers learn how to use tools like boomerangs, bows and arrows, and even a child’s toy to learn speech, and by the end of the show they have a good familiarity with human culture. It’s done in a way that feels like legitimate dinosaurs that have heightened intelligence would do so without going too deep in to humanoid Dinosaurioid territory. One cool detail was each species’ vulnerabilities. Eno is very sensitive to loud noises whereas the Diggers don’t like bright lights and have nictating membranes to try and negate them. These come into play many times in the show by both the heroes and villains, which is something to really give them credit for. As silly as the designs are, it helps sell the illusion that these are still reasonable animals.

To quickly talk about the more technical side of things, the visuals of this movie are nothing you wouldn’t expect in a show of this budget. The CGI on the Dinosapiens is very apparent and though it does do an OK job integrating them with the live action environments at times, other times it can really seem like they’re not there. There’s one episode where Eno protects Lauren and Kit from a grizzly bear, and you can really tell the grizzly is just swatting at nothing. The animation quality can range from surprisingly good to fairly stiff, but the Diggers fare better in this regard than Eno. The sound design is also a bit on the generic side, with both Eno and the Diggers having a lot of stock dinosaur and bird sounds that you’ve heard in other pieces of paleomedia before. The musical score by Rob Lord is also nothing to really write home about, but the opening theme does admittedly set the tone of the show fairly well. On the other hand, the pacing of the show is very solid. It manages to feel like a complete story in all 15 episodes and it has enough time to properly flesh out the story, even if some moments can be a bit of filler. But there’s rarely a point in the show where you’re actively begging for things to stop or move along. To top it all off, the ending ties all loose ends without any cliffhangers to tease a season 2 that will never happen. It knew what story it wanted to tell, it told it the way it wanted, and knew when to stop. I gotta respect a show that does that.

On the whole, Dinosapien is not a masterpiece by any means, but it’s also a harmless dinosaur kid’s show that has its own silly charm to it. It arguably explores the idea of “intelligent dinosaurs” better than the original Dinosauroid idea (cartoony CGI and all), the characters are likeable, and it has a good grasp on its pacing. Much like a lot of Discovery Kids shows, I still have a massive nostalgic soft spot for it, and I recommend it for anyone wanting a piece of paleomedia that you can watch with the entire family.

References Dinosapien (2007) Produced by Corston, J., Randall, J. United Kingdom, Canada: CCI Entertainment, BBC Worldwide.

Naish, D. (2006). Dinosauroids Revisited Darren Naish: Tetrapod Zoology, April 23, 2011.

Russell, D. A.; Séguin, R. (1982). “Reconstruction of the small Cretaceous theropod Stenonychosaurus inequalis and a hypothetical dinosauroid”. Syllogeus. 37: 1–43.

Chances are, when you were a child, you thought dinosaurs were the coolest things ever. Giant reptiles comparable to creatures of myth and legend and the stars of some of the best (and worst) pieces of media of your childhood. And if you are a sensible person, that sentiment carried over into adulthood. Regardless of the quality of a piece of media, the presence of dinosaurs is an ideal way to get it at least some attention and at least a few fans. This is an example of what is called the “Rule of Cool”, in which creative liberties can be forgiven and one’s suspension of disbelief is increased if the media is sufficiently “awesome” or entertaining. Movies, books, and TV shows are typically what people think of when it comes to Paleo-themed “Rule of Cool” media, but one more underappreciated venue is video games, where the Rule of Cool can be turned up to 11. In the 90s and 2000s especially, before Trevorrow’s Jurassic World trilogy suffocated the paleo media genre for a time, there was a myriad of dinosaur-themed video games whose main selling point was emphasizing this rule, such as Turok, Dino Crisis (1 and 2), King Kong: The Official Game of the Movie, the extinct-animal themed packs for the Zoo Tycoon games, and too many Jurassic Park games (both good and bad) to count. Many of these have left strong legacies or at the very least gathered dedicated cult followings over the years, but there was one paleo-themed video game from 2006 that debatably represents the zenith of the “Rule of Cool” and yet has sadly fallen into near-complete obscurity: Paraworld.

Chances are, when you were a child, you thought dinosaurs were the coolest things ever. Giant reptiles comparable to creatures of myth and legend and the stars of some of the best (and worst) pieces of media of your childhood. And if you are a sensible person, that sentiment carried over into adulthood. Regardless of the quality of a piece of media, the presence of dinosaurs is an ideal way to get it at least some attention and at least a few fans. This is an example of what is called the “Rule of Cool”, in which creative liberties can be forgiven and one’s suspension of disbelief is increased if the media is sufficiently “awesome” or entertaining. Movies, books, and TV shows are typically what people think of when it comes to Paleo-themed “Rule of Cool” media, but one more underappreciated venue is video games, where the Rule of Cool can be turned up to 11. In the 90s and 2000s especially, before Trevorrow’s Jurassic World trilogy suffocated the paleo media genre for a time, there was a myriad of dinosaur-themed video games whose main selling point was emphasizing this rule, such as Turok, Dino Crisis (1 and 2), King Kong: The Official Game of the Movie, the extinct-animal themed packs for the Zoo Tycoon games, and too many Jurassic Park games (both good and bad) to count. Many of these have left strong legacies or at the very least gathered dedicated cult followings over the years, but there was one paleo-themed video game from 2006 that debatably represents the zenith of the “Rule of Cool” and yet has sadly fallen into near-complete obscurity: Paraworld. Stina Holmlund, and the wide-eyed Hungarian physicist Béla András Benedek are sent to this world by the leader of the SEAS (Society of Exact Alternative Sciences) Jarvis Babbit for what seems to be an expedition, only for them to realize that his real plan is to subjugate this Para-world as its ruler and seal off any future access by pushing the planet out of orbit via a massive jet engine inside a volcanic crater. For our heroes to stop the SEAs, they bring together the warring tribes and join forces with various disgruntled associates of the SEAs to help, including Babbit’s former assistant Ada Loven, engineer Nikolaj Taslow, naturalist James Warden, the Arch Druid, etc. So yeah, the game’s plot is incredibly derivative (See Avatar, Return of the Jedi, Last Samurai, etc), not to mention extremely dumb. It has plot holes you can drive a school bus through. But it’s also a story that’s not exactly meant to be taken seriously and it has its own corny charm to it. The game’s Rule of Cool factor also helps a lot. Action hero scientists leading warring tribes that ride dinosaurs and mammoths against robotic exo-suits and a giant jet engine inside a volcano is a sentence that is so over-the-top that it needs to be seen to be believed. In addition to this, if some of the aforementioned names seem familiar, a lot of the heroes are very on-the-nose expies of real scientists (Nikolaj Taslow for Nikola Tesla, James Warden for Charles Darwin, Jarvis Babbit for Charles Babbage, etc), but getting to have Darwin and Tesla fight alongside dinosaurs just makes the premise that much sillier to the point of being incredibly entertaining. It makes for both a good laugh and good dose of “Hell yeah”.

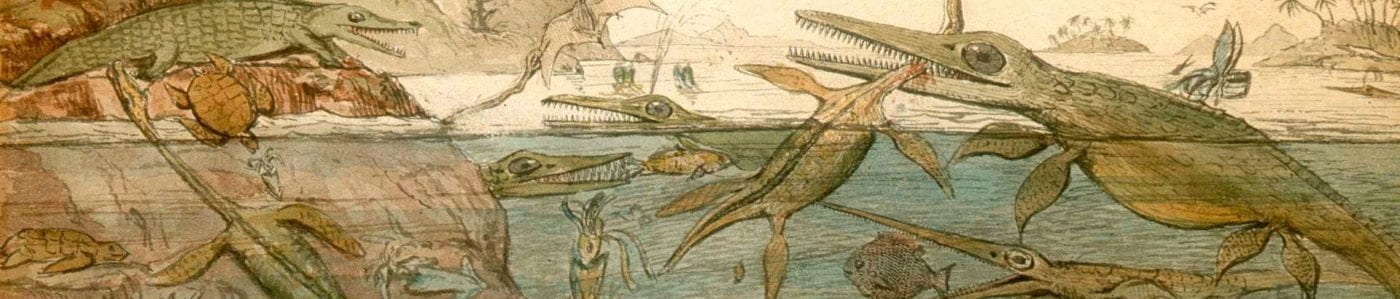

Stina Holmlund, and the wide-eyed Hungarian physicist Béla András Benedek are sent to this world by the leader of the SEAS (Society of Exact Alternative Sciences) Jarvis Babbit for what seems to be an expedition, only for them to realize that his real plan is to subjugate this Para-world as its ruler and seal off any future access by pushing the planet out of orbit via a massive jet engine inside a volcanic crater. For our heroes to stop the SEAs, they bring together the warring tribes and join forces with various disgruntled associates of the SEAs to help, including Babbit’s former assistant Ada Loven, engineer Nikolaj Taslow, naturalist James Warden, the Arch Druid, etc. So yeah, the game’s plot is incredibly derivative (See Avatar, Return of the Jedi, Last Samurai, etc), not to mention extremely dumb. It has plot holes you can drive a school bus through. But it’s also a story that’s not exactly meant to be taken seriously and it has its own corny charm to it. The game’s Rule of Cool factor also helps a lot. Action hero scientists leading warring tribes that ride dinosaurs and mammoths against robotic exo-suits and a giant jet engine inside a volcano is a sentence that is so over-the-top that it needs to be seen to be believed. In addition to this, if some of the aforementioned names seem familiar, a lot of the heroes are very on-the-nose expies of real scientists (Nikolaj Taslow for Nikola Tesla, James Warden for Charles Darwin, Jarvis Babbit for Charles Babbage, etc), but getting to have Darwin and Tesla fight alongside dinosaurs just makes the premise that much sillier to the point of being incredibly entertaining. It makes for both a good laugh and good dose of “Hell yeah”. By contrast, the nomadic Dustriders are incredibly flexible. Inspired by many nomadic African and Middle Eastern tribes in our own world, they can take down their buildings and retrieve the resources needed to build them back, allowing them to quickly dismantle their camps and move them to a more suitable location. Along with this reliance on mobility, the Dustriders are also specialized in cavalry, using massive dinosaurs such as Ankylosaurus, Stegosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus as powerful combat units that can be upgraded with coats of bone armor. Many of these dinosaurs can also be converted at will, so a Brachiosaurus can be quickly converted to an artillery unit with a massive catapult on its back to shoot poisonous rocks at buildings and then revert to a close combat unit in seconds. This even extends to their naval fleets. While they have long range catamarans, most of their naval ships are marine reptiles such as Macrochlemys and Kronosaurus.

By contrast, the nomadic Dustriders are incredibly flexible. Inspired by many nomadic African and Middle Eastern tribes in our own world, they can take down their buildings and retrieve the resources needed to build them back, allowing them to quickly dismantle their camps and move them to a more suitable location. Along with this reliance on mobility, the Dustriders are also specialized in cavalry, using massive dinosaurs such as Ankylosaurus, Stegosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus as powerful combat units that can be upgraded with coats of bone armor. Many of these dinosaurs can also be converted at will, so a Brachiosaurus can be quickly converted to an artillery unit with a massive catapult on its back to shoot poisonous rocks at buildings and then revert to a close combat unit in seconds. This even extends to their naval fleets. While they have long range catamarans, most of their naval ships are marine reptiles such as Macrochlemys and Kronosaurus. primitive weaponry, the SEAS have legitimate firearms such as muskets, machine guns and cannons. Additionally, they have steam-powered mechanical units ranging from motion-capture exosuits to vaguely dinosaur-shaped mechas, some of which are also equipped with machine and gatling guns. This is one area where even the “Rule of Cool” factor had to be sacrificed for the sake of gameplay. While seeing 20th century tanks and ships fight armies of dinosaurs would be the zenith of the “Rule of Cool”, it would only be for the short term. Realistically, the invading force with modern technology would have little difficulty wiping out more primitive tribes and the game required to make a few compromises to make it as fair as possible. Along with some questionable balancing (Gatling guns not melting down health in 5 seconds flat), 20th century weapons such as tanks and jets were not included and had to be replaced by the exosuits, things that dinosaur cavalry would have a fighting chance against. In addition, the tribes were equipped with their own tanks and heavy armor, which helps even the odds. While most of the game’s gameplay/story issues can be tolerated with “Rule of Cool”, they made the right call in sacrificing a bit of it to be as fair a fight as possible.

primitive weaponry, the SEAS have legitimate firearms such as muskets, machine guns and cannons. Additionally, they have steam-powered mechanical units ranging from motion-capture exosuits to vaguely dinosaur-shaped mechas, some of which are also equipped with machine and gatling guns. This is one area where even the “Rule of Cool” factor had to be sacrificed for the sake of gameplay. While seeing 20th century tanks and ships fight armies of dinosaurs would be the zenith of the “Rule of Cool”, it would only be for the short term. Realistically, the invading force with modern technology would have little difficulty wiping out more primitive tribes and the game required to make a few compromises to make it as fair as possible. Along with some questionable balancing (Gatling guns not melting down health in 5 seconds flat), 20th century weapons such as tanks and jets were not included and had to be replaced by the exosuits, things that dinosaur cavalry would have a fighting chance against. In addition, the tribes were equipped with their own tanks and heavy armor, which helps even the odds. While most of the game’s gameplay/story issues can be tolerated with “Rule of Cool”, they made the right call in sacrificing a bit of it to be as fair a fight as possible. So, this all begs the question: Why did the game fail? How did a game that is “Rule of Cool” personified become such a flop? Well, there were several factors. For one, it came out at a time where RTS games already had their day. By 2006, the genre’s peak in popularity with games like Starcraft, Warcraft 3, and Age of Empires was a distance memory and PC gaming was slowly being outcompeted by consoles such as Nintendo, Playstation and Xbox. It was extremely difficult for RTS games to carve their niche into the market at a time where first person shooters and open world games were gaining significant traction. So Paraworld had a severe case of bad timing. For two, when the “Rule of Cool” factor that the game relied on was peeled away, there wasn’t much left to help it stand out against its counterparts. Paraworld’s mechanics and gameplay loop, while smooth, was derivative of Age of Empires to the point that many reviews had pointed out the comparison. Even the Army Controller mechanic was a bit of a mixed bag. On the one hand, it allows you to properly micromanage your armies and check on each and every one of your units. But on the other hand, the limit of 52 units and the way it’s structured results in the battles being small in scale and limits what kind of armies you could make. These factors simply added up and created a recipe for commercial disaster and it resulted in a game that me and maybe 12 other people in the entire world still remember.

So, this all begs the question: Why did the game fail? How did a game that is “Rule of Cool” personified become such a flop? Well, there were several factors. For one, it came out at a time where RTS games already had their day. By 2006, the genre’s peak in popularity with games like Starcraft, Warcraft 3, and Age of Empires was a distance memory and PC gaming was slowly being outcompeted by consoles such as Nintendo, Playstation and Xbox. It was extremely difficult for RTS games to carve their niche into the market at a time where first person shooters and open world games were gaining significant traction. So Paraworld had a severe case of bad timing. For two, when the “Rule of Cool” factor that the game relied on was peeled away, there wasn’t much left to help it stand out against its counterparts. Paraworld’s mechanics and gameplay loop, while smooth, was derivative of Age of Empires to the point that many reviews had pointed out the comparison. Even the Army Controller mechanic was a bit of a mixed bag. On the one hand, it allows you to properly micromanage your armies and check on each and every one of your units. But on the other hand, the limit of 52 units and the way it’s structured results in the battles being small in scale and limits what kind of armies you could make. These factors simply added up and created a recipe for commercial disaster and it resulted in a game that me and maybe 12 other people in the entire world still remember. Survival Evolved serves as a clear spiritual successor, its lackluster gameplay mechanics, mixed bag of creature designs, infamously bad optimization, and lack of direction makes it a somewhat poor follow-up that fails to replicate Paraworld’s charm. Between its smooth, if derivative, gameplay, incredible musical score, appealing art direction, an entertainingly silly story and a nice variety of tribes complete with prehistoric creatures to lead into battle, Paraworld is the personification of the inherent “Rule of Cool” factor of paleomedia, for better and for worse.

Survival Evolved serves as a clear spiritual successor, its lackluster gameplay mechanics, mixed bag of creature designs, infamously bad optimization, and lack of direction makes it a somewhat poor follow-up that fails to replicate Paraworld’s charm. Between its smooth, if derivative, gameplay, incredible musical score, appealing art direction, an entertainingly silly story and a nice variety of tribes complete with prehistoric creatures to lead into battle, Paraworld is the personification of the inherent “Rule of Cool” factor of paleomedia, for better and for worse.

I was delighted to find my photograph Still Life with Fossil Seafood accepted for the Royal Academy “Summer” Exhibition this year. They say “summer” but it has only just opened to the public and goes on until 2 January. So, maybe more of a Devensian or Anglian summer, but with shorter days. However, when you go into the show it has the colour and energy of the brightest summer. It is also available to view online

I was delighted to find my photograph Still Life with Fossil Seafood accepted for the Royal Academy “Summer” Exhibition this year. They say “summer” but it has only just opened to the public and goes on until 2 January. So, maybe more of a Devensian or Anglian summer, but with shorter days. However, when you go into the show it has the colour and energy of the brightest summer. It is also available to view online

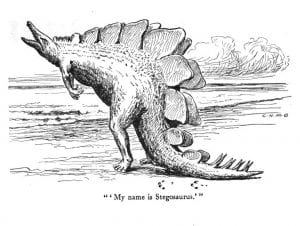

Sternberg’s prose is colorful. He paints vivid pictures that, although dated by today’s science, are evocative of a lost era. Here he describes the battle between a Trachodon and a Gorgosaurus:

Sternberg’s prose is colorful. He paints vivid pictures that, although dated by today’s science, are evocative of a lost era. Here he describes the battle between a Trachodon and a Gorgosaurus:

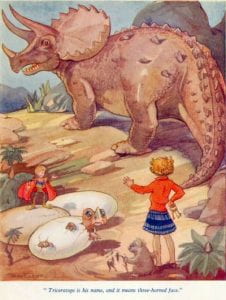

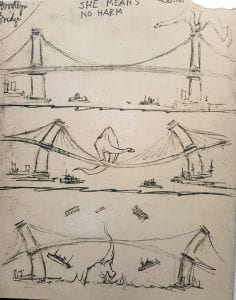

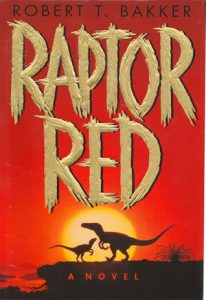

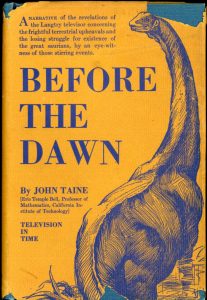

1934’s Before the Dawn by John Taine (pen name of Eric Temple Bell) is perhaps the first novel featuring dinosaur protagonists, predating Bakker’s novel by sixty-one years. The book’s prehistoric scenes are framed by scientists watching the beasts through some kind of time screen. One of the men has devised a means of replaying a residue of light within crystals just as someone might play grooves left by sound on an LP. The pseudoscience is beside the point, it’s just a vehicle to get to the dinosaurs.

1934’s Before the Dawn by John Taine (pen name of Eric Temple Bell) is perhaps the first novel featuring dinosaur protagonists, predating Bakker’s novel by sixty-one years. The book’s prehistoric scenes are framed by scientists watching the beasts through some kind of time screen. One of the men has devised a means of replaying a residue of light within crystals just as someone might play grooves left by sound on an LP. The pseudoscience is beside the point, it’s just a vehicle to get to the dinosaurs.