Our first specially written guest post! Benjamin is an American teacher working in Slovakia. He has a life-long love of dinosaurs and all things prehistoric. He runs the Twitter feed @paleo_pop and the (semi-retired) Tumblr Antediluvian Echoes. I “met” Benjamin through his fascinating Twitter feed and asked him to write a piece for us. Here it is – with my thanks.VC

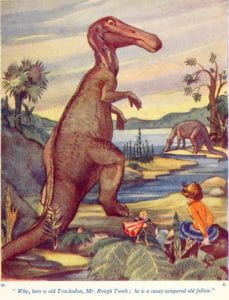

Fossils have a way of firing the imagination. Finding shells where there is no sea or uncovering bones of massive, unusual beasts has sparked ideas since ideas could be had. Fossils were imagined to be relics of Thor’s thunder-strikes, bones of dragons, and evidence of Noah’s Flood. As paleontology turned fossils from mythical curios to scientific artifacts, so too did people’s imaginations shift from describing fossils with fantastical stories to using them to explain the history of life on Earth. British academic Henry Morley did so in writing one of the first examples of paleofiction in “Our Phantom Ship on an Antediluvian Cruise” (1851). His essay invited readers to journey on a fantastical boat, sailing through space and time to visit prehistoric flora and fauna—“Monsieur the Mylodon” consuming a tree; a muddy, peeping ichthyosaur; and tree fern forests brushing against the sky; among other sights. By using the framework of a time-traveling ship, Morley provided a narrative device to explain the reader’s antediluvian sightseeing. He would not be the last to do so. Teaching paleontology via a fictional “time tour” has become a popular framework for science education, especially in children’s natural history books.

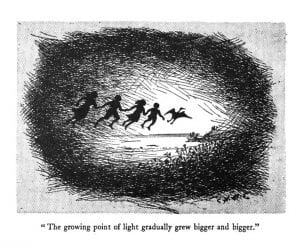

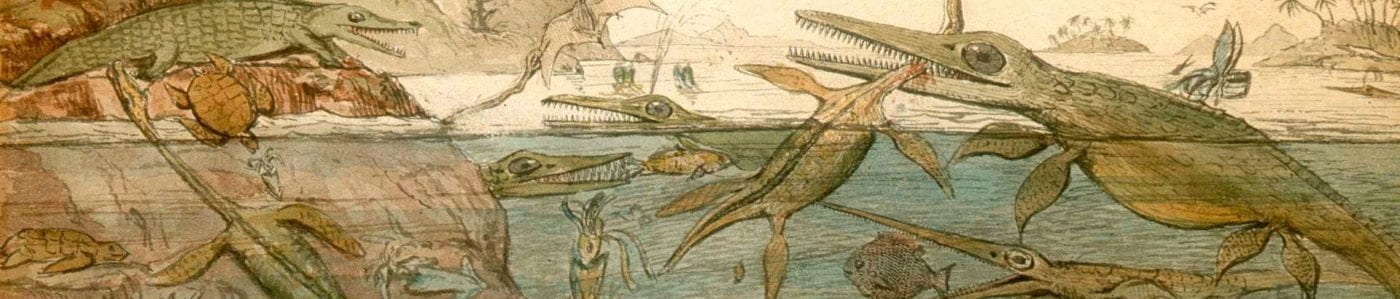

An early example of this is 1924’s Dragons at Home, by C. H. Murray Chapman. Printed in London, the book follows the adventures of four children—Rupert, who loves dinosaurs, and Helen, Dick, and Di who are either apathetic towards fossils or doubtful of their authenticity. (It is curious how many authors describe their chrononauts as starting their adventure doubting dinosaurs even existed. In my experience, it is usually adults who cannot fathom dinosaurs; children are eager to believe.) Paging through a dinosaur book, Rupert wishes he could see extinct animals in the flesh. His wish is so strong, it resurrects a talkative pterodactyl which guides them to the past. Chapman does not seem too interested in explaining the means of the kids’ time travel; they just sort of fall though darkness and “the Sigh of the Ages”, landing in the Mesozoic. There the pterodactyl introduces the children to a Stegosaurus who thinks itself a poet, a German-speaking Archaeopteryx, and a pair of sauropods. The

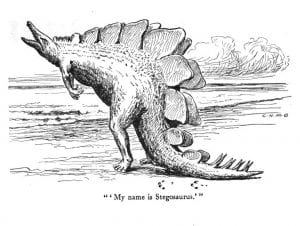

An early example of this is 1924’s Dragons at Home, by C. H. Murray Chapman. Printed in London, the book follows the adventures of four children—Rupert, who loves dinosaurs, and Helen, Dick, and Di who are either apathetic towards fossils or doubtful of their authenticity. (It is curious how many authors describe their chrononauts as starting their adventure doubting dinosaurs even existed. In my experience, it is usually adults who cannot fathom dinosaurs; children are eager to believe.) Paging through a dinosaur book, Rupert wishes he could see extinct animals in the flesh. His wish is so strong, it resurrects a talkative pterodactyl which guides them to the past. Chapman does not seem too interested in explaining the means of the kids’ time travel; they just sort of fall though darkness and “the Sigh of the Ages”, landing in the Mesozoic. There the pterodactyl introduces the children to a Stegosaurus who thinks itself a poet, a German-speaking Archaeopteryx, and a pair of sauropods. The children travel through a few more epochs with other animals as their guides, chatting with an overly-sensitive Iguanodon and a Deinotherium and mastodon pair that wax at length about their family’s dynasty. At the book’s end, the children return to their own time and visit the Natural History Museum at night. The ghosts of their prehistoric docents give a final good-bye from the fossil exhibits.

children travel through a few more epochs with other animals as their guides, chatting with an overly-sensitive Iguanodon and a Deinotherium and mastodon pair that wax at length about their family’s dynasty. At the book’s end, the children return to their own time and visit the Natural History Museum at night. The ghosts of their prehistoric docents give a final good-bye from the fossil exhibits.

Chapman illustrated the book himself. His pen and ink drawings are scribbly, sometimes cartoonish. Few will suggest his reconstructions are scientifically accurate—even by the standards of his era—but considering the animals all speak (and are quite chatty!) and tend to split their genera names into friendly fore- and surnames (e.g., Archie Opteryx and Hesper Ornis), the drawings match the playful tone of the text.

Chapman illustrated the book himself. His pen and ink drawings are scribbly, sometimes cartoonish. Few will suggest his reconstructions are scientifically accurate—even by the standards of his era—but considering the animals all speak (and are quite chatty!) and tend to split their genera names into friendly fore- and surnames (e.g., Archie Opteryx and Hesper Ornis), the drawings match the playful tone of the text.

Dragons was published posthumously. Chapman was a pilot by trade and was sadly killed in a flight accident at the onset of World War I. His prose is jaunty and imaginative, so it is a pity his early death prevented more books in his voice from being published.

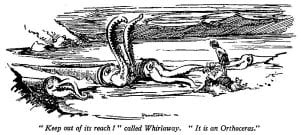

Similar to Dragons at Home is Whirlaway: A Story of the Ages, written by H. C. F. Morant and illustrated by Jean Elder. Published in 1937 for Australian readers, Whirlaway begins with twelve-year-old Helen (another Helen!) wandering through the pages of a natural history book. A bit bewildered by the images of prehistoric beasts, she gazes into the fireplace to watch the embers crackle in the flames, remembering that her father “had said that every spark in the fire was a sunbeam that had shone, millions of years ago, on the plants that had formed the coal.” Suddenly one of the coals pop, and from it emerges an elf—literally a living sunbeam trapped in the coal for 100 million years—who Helen names Whirlaway. The two discover a trapdoor in the floor of Helen’s home and through it they sink deep into the earth, passing through additional doors which lead to vistas of various geologic eras. Helen nearly stumbles into the waving arms of an Orthoceras, gets spooked by a flock of pterosaurs, watches a Tyrannosaurus struggle to the death in a bog, and thrills to an Arsinoitherium defending itself against predators.

and illustrated by Jean Elder. Published in 1937 for Australian readers, Whirlaway begins with twelve-year-old Helen (another Helen!) wandering through the pages of a natural history book. A bit bewildered by the images of prehistoric beasts, she gazes into the fireplace to watch the embers crackle in the flames, remembering that her father “had said that every spark in the fire was a sunbeam that had shone, millions of years ago, on the plants that had formed the coal.” Suddenly one of the coals pop, and from it emerges an elf—literally a living sunbeam trapped in the coal for 100 million years—who Helen names Whirlaway. The two discover a trapdoor in the floor of Helen’s home and through it they sink deep into the earth, passing through additional doors which lead to vistas of various geologic eras. Helen nearly stumbles into the waving arms of an Orthoceras, gets spooked by a flock of pterosaurs, watches a Tyrannosaurus struggle to the death in a bog, and thrills to an Arsinoitherium defending itself against predators.

The animals do not talk in this book. Instead, Whirlaway—being a spot of light and therefore very old and knowledgable—teaches Helen about each era and creature they encounter. Although having a beam of light as a guide is novel, the elf-like nature of Whirlaway harkens to an earlier time-travel docent: 1861’s Paris Before Man by Pierre Boitard has the author taken through time on a flying rock by an impish demon with a bum leg. However, Boitard’s demon does not break into song like Whirlaway, such as his ditty about why trilobites evolved eyes.

The animals do not talk in this book. Instead, Whirlaway—being a spot of light and therefore very old and knowledgable—teaches Helen about each era and creature they encounter. Although having a beam of light as a guide is novel, the elf-like nature of Whirlaway harkens to an earlier time-travel docent: 1861’s Paris Before Man by Pierre Boitard has the author taken through time on a flying rock by an impish demon with a bum leg. However, Boitard’s demon does not break into song like Whirlaway, such as his ditty about why trilobites evolved eyes.

Elder’s illustrations for Whirlaway are a bit less fanciful than Chapman’s for Dragons at Home. There are blasts of steam coming from a hungry Inostrancevia, anchisaurs battling by nipping each other’s tails, and a Scelidosaurus stomping about upright like an Ultraman monster—“This animal is called Beef Ribs,” claims the caption—but for the most part the reconstructions are more accurate for the era than not. Eagle-eyed readers might notice a few “homages” among Elder’s drawings to images by other artists like Gerhard Heilmann or Charles R. Knight.

coming from a hungry Inostrancevia, anchisaurs battling by nipping each other’s tails, and a Scelidosaurus stomping about upright like an Ultraman monster—“This animal is called Beef Ribs,” claims the caption—but for the most part the reconstructions are more accurate for the era than not. Eagle-eyed readers might notice a few “homages” among Elder’s drawings to images by other artists like Gerhard Heilmann or Charles R. Knight.

Copies of Whirlaway are rare. The book’s publication was ill timed. As European antagonism intensified at the end of the 1930s, few shipments of books reached Australia from London printers, and the majority of the unsent Whirlaway book stock was destroyed in the Blitz. Morant’s planned sequel, The Ether Chariot, a book about astronomy, was never realized.

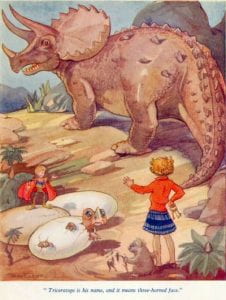

Life Story by Virginia Lee Burton may be the best known of the books described here as it has been in print the longest. Originally published in the U.S. in 1962, it has never been out of print. Burton’s book takes its reader through time via the framework of a theater production. It sometimes feels like a cosmic version of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Narrators of different specialties (an astronomer, a paleontologist, etc.) lead the readers through epochs of time glowing on the stage, starting with the birth of the Milky Way and ending with a spring morning outside the reader’s window. The pages between feature a colorful panoply of mountains heaving, forests thriving, dinosaurs prowling, whales spouting, and people building.

here as it has been in print the longest. Originally published in the U.S. in 1962, it has never been out of print. Burton’s book takes its reader through time via the framework of a theater production. It sometimes feels like a cosmic version of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Narrators of different specialties (an astronomer, a paleontologist, etc.) lead the readers through epochs of time glowing on the stage, starting with the birth of the Milky Way and ending with a spring morning outside the reader’s window. The pages between feature a colorful panoply of mountains heaving, forests thriving, dinosaurs prowling, whales spouting, and people building.

The illustrations are stylized and painted in dreamy colors, with phantom blacks butting against lurid yellows, pinks, and greens. Superficially, Life Story is a bit reminiscent of “The Rite of Spring” sequence from Fantasia, though Burton’s retelling is certainly her own. The book’s text was updated in 2009 to reflect changes in nomenclature—Brontosaurus becomes Apatosaurus, for example—but the images remained untouched.

The illustrations are stylized and painted in dreamy colors, with phantom blacks butting against lurid yellows, pinks, and greens. Superficially, Life Story is a bit reminiscent of “The Rite of Spring” sequence from Fantasia, though Burton’s retelling is certainly her own. The book’s text was updated in 2009 to reflect changes in nomenclature—Brontosaurus becomes Apatosaurus, for example—but the images remained untouched.

Many of Burton’s children’s books deal with change: The Little House describes the life of a tiny home and the transforming landscape around it as suburbs become cities and so on. Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel is built on the themes of technology’s progress and overcoming obsoletion. Life Story is no different, with its theater show of life and environments parading across billions of years. As the book progresses, the spans of time between the “scenes” shorten, starting with eons and ending with hours. It is an effective means of conveying the intimate finiteness humans experience in the infinite vastness of time and space. In that way, Life Story is a humbling book, yet its last words are empowering, reminding the reader that they are part of the Life Story—“each passing second a new link in the endless chain of Time”—and inviting them to be the next lead the drama.

All of these books are available for reading online. Dragons at Home is on Hathitrust; Whirlaway is on Austalia’s Gutenberg website; and Life Story can be read on archive.org. The copy of Life Story that some generous soul uploaded to archive features an inscription written by anonymous grandparents. The words were meant only for the reader of that particular copy of Life Story, but, now shared, they could be addressed to anyone exploring natural history through the magic of a book: “We continue to learn more and more … a continuous story … what new kinks will you discover in your lifetime? May you always experience the joys … and the questions discoveries present!”

Vicky, I am enjoying you Paleomedia posts, especially this one about children’s dinosaur books.

They look lovely. The information at the bottom of Benjamin Chandler’s article is useful and I plan to read the books.

I’m waiting though for you to write and illustrate your own book.

All the best to you and Steve.

Steve Burns