by Mikolaj Skakuj

It is time to meet dragons… again! In this post, I would like to address what seem to be the core serpentine characteristics inherent to dragons and point to instances of a re-emphasis on those features.

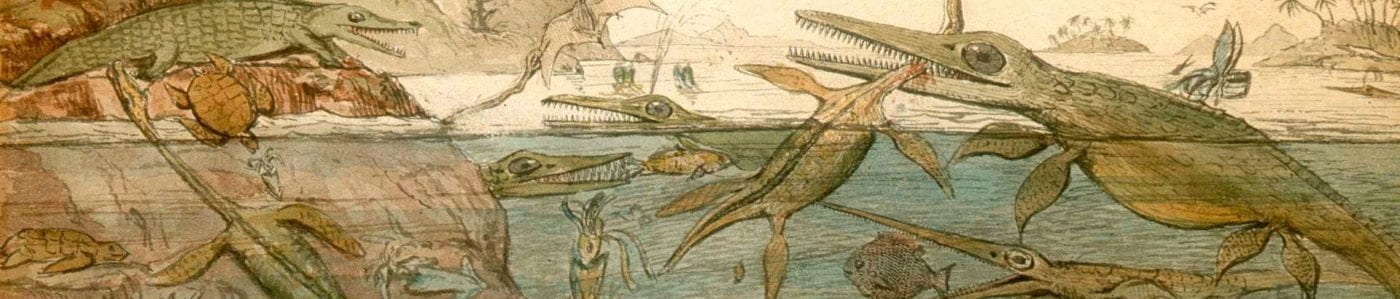

As previously mentioned on this blog, dragons are among the few mythical creatures to capture the popular imagination so readily (Green, 2021; Pollard, 2023). With this popularity comes great variety. Unfortunately, the variety contributes to acrimonious discussions on what is and is not a dragon, and one is left with only some vague intuition of what it is. Fortunately, a 2013 team of scientists applied phylogenetic methods to draconic myths and found that all dragons can be traced to a single serpentine origin in Africa, as previously discussed by Pollard (2023).

Traces of the serpentine origin can be seen in the stereotypical Western dragon of modern fantasy, namely the long and often flexible necks able to make snakish bends. Chinese dragons especially resemble giant snakes, except with four limbs and various exaggerations. In addition, the Ancient Greek word drákon (the etymological ancestor of the English dragon) can also mean serpent (Morwood and Taylor, 2002, p. 90).

Thus, we can attempt at a comprehensive and universal definition for all draconic beasts.

Dragon = a serpent or snake, monstrous or with exaggerated features, or any iteration/derivative thereof.

Under this definition, the cockatrice (in Polish synonymized with the basilisk) is a dragon with rooster features; the wyvern is type of dragon, rather than a distinct creature; and the Melusine (a beautiful women with two serpentine tails beneath the waist) is a female half-human, half-dragon hybrid.

The definition nicely encompasses a vast majority of what most people consider dragons, big and small. Furthermore, one no longer needs to rely on additions of flying and fire-breathing (which are in common with other creatures, e.g., the griffin). However, an increasing number of popular culture variants tend to depart from the core serpentine features, although they could still be recognized as squamates (e.g., dragons from the How To Train Your Dragon (Sanders and DeBlois, 2010) sheds epidermal scales and have forked tongues). At one extreme, dragon designs may lose so much of the core traits, trading long necks for short ones and massive skulls in the case of the Gronckle, that people of the antiquity may not have recognize them as such, if not for the wings and fire.

However, we can also observe instances of the opposite trend. Within the How to Train Your Dragon film franchise, we have the Whispering Death, a rock-drilling dragon with only wings for limbs. Although the oversized and rather round heads are still unusual, the elongate and flexible body would surely be eerily familiar to any ancient Greek citizen. It even slithers when grounded. A giant mutant version of this dragon appears in The Defenders of Berk (season 2 of Dreamworks Dragons, (Brown and Sloan, 2012-2014)) and is known as the albino Screaming Death. Both those dragons can shoot spines, the look of which could recall the appearance of certain vipers.

Such serpentine reversions had precedent in pre-modern mythology. In the next example, the reversion was almost complete. I shall introduce the King of Snakes, with its golden crown, an icon of Polish legends.

The character is morally ambivalent. Bartłomiej Grzegorz Sala (2024) notes that in one legend from Cieszyna, the King of Snakes is a prince, who was cursed by his wicked mother, the Black Duchess, simply for falling in love with a maid. For once, a monster is the victim. In another from the Jura area, he is a draconic beast that terrorized the people. Elsewhere, he is neutral (and a plain snake), only going after the protagonist when he tries to steal some of its treasure.

Sala (2024, pp. 15 and 88) is almost certain that the King of Snakes was derived from another Slavic creature, itself ambiguous with regards to intention and whether there was one (in several forms) or many individuals. The Żmij (also Zmij) is sometimes an enemy of people, appearing in one legend from Ukraine as a seven-headed dragon that breathed fire, but can also be their friend. To make matters more complicated, it has also been depicted as a petty, serpentine thief, stealing milk, money or grain depending on the variant legend. The link between the King of Snakes and Żmij could be supported by the fact that the latter also wears a golden crown in the legend of Żmigród, Poland (Sala, 2024, pp. 17-20 and 88).

The last case of a dragon reverting to more serpentine characteristics I wish to mention is perhaps the greatest fire drake to ever be conceived: Smaug the Golden.

The English audience should be at least somewhat familiar with JRR Tolkien’s iconic creation in The Hobbit but for the rest of us let us recap: Smaug was a great wyrm of the North, who flew southwards to devast the City of Dale and oust the dwarves of Erebor, the Lonely Mountain, gaining a sickly wealth for over 160 years, until Thorin Oakenshield’s company arrived and set off his ultimate downfall at the hands of Bard the Bowman and his Black Arrow. It is worth mentioning that Smaug is extremely intelligent and speech-capable, elements taken from Fafnir of Norse myth (Pellerin, 2009, p. 16 and references within). Incidentally, ancient people of the Middle East and Egypt revered snakes as cunning and crafty.

We know from a drawing how JRR Tolkien himself envisioned Smaug. The illustration, Conversation with Smaug, depicts a lizard-like creature with bat-wings as an extra pair of limbs and an elongate body with an especially long tail. The legs are small and, curiously, the head boasts cat-like ears. In short, Smaug resembles some of Bristol’s dragons of Medieval tradition (see Jones, 2023).

Smaug steered away from his lepidosaurian roots when Rankin/Bass re-designed him in an animated adaptation of The Hobbit (Rankin Jr. and Bass, 1977). There, the legs are more fully developed, the torso is stockier (and fatter… do not mention this to Smaug!), fur grows on his back and the head is far more feline.

The most iconic rendition of Smaug is that of Peter Jackson’s (2012-2014) trilogy. There, he is at his largest (why is it that size gets greatly exaggerated with pop culture dragons?) and his wings and forelegs became the same set of limbs. Despite the retention of limbs, Smaug is much more serpentine, with a much longer neck that is flexible and muscular, and a proportionally smaller torso. The way he moves in The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (Jackson, 2013)… you could almost swear that he slithers. His eyes have slit pupils, like snakes that rely on ambush (although the trait is also feline).

As well as in his physical features, Smaug is also a snake in character. Already utterly proud and cruel in the book, the Jackson rendition is outright sadistic, psychologically tormenting Bilbo Baggins and enjoying the prospect of Thorin being corrupted by the Arkenstone. Moreover, it is mentioned in The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies (Jackson, 2014) that Smaug was in league with the Dark Lord Sauron; The Desolation of Smaug (Jackson, 2013) hints at this when the dragon foresees that a “darkness is coming” and it “will spread to every corner of the land”. It appears that this iteration of Smaug had additionally reverted to the hellish dragon-devil archetype of Christian tradition, which might explain his popularity.

So, there you have it: three instances of dragons returning to their serpentine origins. First, the Whispering Death is a menace in How to Train Your Dragon. Secondly, the King of Snakes probably descended from the Żmij in Poland. And last, but not least, Smaug of many titles received the treatment from Peter Jackson and his creative team.

References

Brown, A. and Sloan, D. 1-2 (2012-2014) ‘Dreamworks Dragons’ [DVD]. 07/08/2012-05/03/2014. United States: Twentieth Century Fox.

Green, E. (2021) ‘Guest post: How To Evolve Your Dragon: Dragons Under Natural Selection’, Palaeomedia. Available at: https://palaeomedia.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2021/08/22/guest-post-how-to-evolve-your-dragon-dragons-under-natural-selection/ (Accessed: 26/11/2024).

The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (2013) Directed by Jackson, P. [Blu-Ray]. Denmark: Warner Brothers Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures.

The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies (2014) Directed by Jackson, P. [Blu-Ray]. Denmark: Warner Brothers Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures.

Jones, E. (2023) ‘The Bristol Dragons’, Palaeomedia. Available at: https://palaeomedia.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2023/02/08/the-bristol-dragons/ (Accessed: 26/11/2024).

Morwood, J. and Taylor, J. (eds.) (2002) The Pocket Oxford Classical Greek Dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pellerin, C. (2009). Putting the Spotlight on Smaug. Bachelor Honours, Rhode Island College.

Pollard, S. (2023) ‘Darwinism and Dragons’, Palaeomedia. Available at: https://palaeomedia.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2023/03/31/darwinism-and-dragons/ (Accessed: 26/11/2024).

The Hobbit (1977) Directed by Rankin Jr., A. G. and Bass, J. United States.

Sala, B. G. (2024) Księga smoków polskich [Translated title: The Book of Polish Dragons]. 2nd, reprint edn. Poland: BoSz.

How to Train Your Dragon (2010) Directed by Sanders, C. and DeBlois, D. [Blu-Ray]. United States: Dreamworks Animation SKG.