This is a guest post from The Bristol Dinosaur Project blog. With thanks to Rhys Charles for the share.

Guest Author: James Ormiston

James Ormiston graduated from the Palaeontology & Evolution MSci at the University of Bristol in 2016. He is now a palaeoartist (@notsimro) and lab technician.

Bridging the Gap

So far what I’ve done is over a thousand words of moaning, and excessive moaning adds fuel to the weird factionalism that’s appeared in the wake of this debate. So, what can actually be done about it? It was good to see Colin Trevorrow finally take on board peoples’ concerns over the lack of feathers, and getting the well-known dinosaur palaeontologist Prof Steve Brusatte (of the University of Edinburgh) on board for ‘JW: Dominion’ as an advisor is encouraging. For the most part however, the Jurassic franchise is something of a lost cause when it comes to accuracy as it’s already out there. It has its own extended universe, with spin-offs and video games, now cemented in modern culture – pronated hands and all.

Unless Dominion is radically different, or Universal suddenly decide to make their own documentary addressing the movies’ scientific flaws, the damage is mostly done. It is indeed mainly for entertainment, and huge numbers of people enjoy it because the movies are fun to watch. Maybe we should just bury the hatchet and focus our efforts elsewhere? After all, the movies are still huge adverts for STEM subjects, even if they are now much more like fan fiction than love letters. We should steer young prospective palaeontologists, science enthusiasts and dinosaur fans of the future in the right direction, rather than turn them away by simply nit-picking at their ticket in (and I say this as someone 100% guilty of doing the latter in this very article – it’s easy to get carried away!).

Let’s compare palaeontology’s media presence to its bigger physics-based brother: space exploration. Unlike palaeontology, which has essentially one big live-action franchise and nothing else, space has had a continual presence in cinema for decades. It has had the time and opportunities to incorporate more and more real-world science. Things like the lack of sound in space, how gravity works and what a black hole may look like.

Yes, there are still many unrealistic aspects because the audience needs to be engaged, but the key difference is that many different directors have had a go and at least tried to make their movies more convincing. Just look at the plethora of big budget space releases we’ve had since Gravity came out: Interstellar, The Martian, Ad Astra, and series like The Expanse. How often do you see dinosaurs in non-cartoon films outside of the Jurassic franchise, and when you do, how well-researched are they?

This monopoly over dinosaurs’ public image should ideally be broken. The public needs a bigger and more accessible yardstick to compare with the Jurassic franchise. They should be easily able to say “the dinosaurs in those movies are inaccurate, they should look more like this”. Not just because I’m telling them to through outreach efforts, but because the public likes dinosaurs and deserves something that lets them do it themselves. Currently though, this does not exist in popular culture. Walking With Dinosaurs came out over 20 years ago. It may have been the closest thing to rival the movies for the public’s attention, but soon afterwards it too was outdated (the same goes for its follow-up, Planet Dinosaur, though to a lesser extent). It just happened to be unlucky timing, in that it came out just before the main swing of the feather revolution and other breakthroughs of the 21st century. Space science already had its Walking With Dinosaurs moment with Carl Sagan’s 1980 series Cosmos, which returned to great praise with physicist and sci-comm juggernaut Neil deGrasse Tyson in 2014. It’s about time palaeontology got its next big public update too.

For larger studios this shouldn’t be difficult given their enormous budgets. All it takes is more engagement with the research community, to hire advisors who know their stuff and a willingness to listen to them. Even Jurassic Park 3 was starting to update things, as Stan Winston’s design team gave the raptors little head quills (in 2001!). The 2013 Walking With Dinosaurs movie also managed a good amount of communication with scientists, and although it wasn’t much of a critical success it gave us a glimpse of what was possible (also worth noting that critics liked the well-researched and visually impressive animation, but not the cheesy voiceover story which 20th Century Fox insisted on adding late in production, fearing the public would become bored otherwise, i.e. they didn’t want to risk doing something different). There have also been ambitious real-world immersive experiences like Dinosaurs in the Wild (which I had the immense privilege to work at in 2017). Projects like this have big potential, and if done right could fill a significant gap in the market.

The Nerds Fight Back and Hope for the Future

One of the biggest hurdles to clear when getting the public up to speed is that there are many places to get information about dinosaurs (and prehistoric life in general) but not all of it is updated and reliable. Wikipedia is generally a good place because many palaeontologists, especially those working on dinosaurs, actively update Wikipedia articles to include their most recent work on them. While this does result in some very long overly-academic sections where competing research teams have a bit of a back-and-forth over certain issues, at least readers can see what is still debated and why.

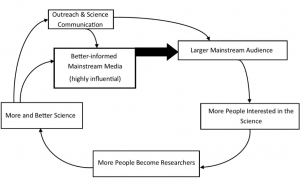

Outside of Wikipedia, which is often a dry read and as a result off-putting to the layperson, where can the public go for good, engaging palaeontological information? After all, there’s a lot of clickbait out there alongside piles of stuff from other inaccurate media and the Jurassic franchise itself. It also doesn’t help at all that mainstream news can be very patchy when it comes to reporting almost anything in the field. Here’s where the outreach and science communication community steps in. Whether it be museums, academics or enthusiasts, we live in an exciting time when the public is increasingly able to get well-researched content presented to them on familiar formats such as YouTube, livestreams and podcasts.

You can tune into hour-long live discussions hosted by museums with current researchers answering questions in real time (no doubt bolstered by recent boom in video calling thanks to the current situation!). You can listen to podcasts by people passionate about the science of palaeontology dispelling misconceptions, interviewing experts, relaying the latest and most interesting discoveries, or going over the basics for the uninitiated. Thanks to channels like PBS Eons you can watch mini-documentaries on YouTube with accurate palaeoart to bring the prehistoric world to life, and we’re seeing an increase in small networks and indie studios making their own features. There are other projects aiming to catalogue up-to-date information together into consistent, easily comprehensible online resources like the pterosaur archive Pteros.

In physical literature we are seeing a great array of popular science books about prehistoric life and its reconstruction being published – with the non-academic reader in mind. Palaeoartists are banding together to make accurate and beautiful prehistoric-themed merchandise for decorating your home and self. You can also now buy very well-designed and researched toys and models thanks to efforts like Beasts of the Mesozoic and the PNSO dinosaur series.

It’s even happening to video games, among the most exciting upcoming examples being Prehistoric Kingdom – a park simulator in a similar vein to the popular Jurassic World: Evolution, but for those who want to look after animals rather than movie monsters. Similar improvement is increasingly happening for content aimed specifically at children (obviously, since children are among the biggest dinosaur fans of all and represent a huge market), though not being a parent I’m less familiar with that side of things.

All these efforts serve to re-connect the public to the ever-changing world of palaeontology research. It’s a link that the original Jurassic Park made an effort to strengthen but Jurassic World generally did not. Will mainstream media pick up on this increasing momentum? It would seem this is indeed finally happening! A couple of years ago Apple TV greenlit a major new dinosaur series with BBC Studios’ Natural History Unit, to be called Prehistoric Planet. Among the team working on it were reported Jon Favreau (of Iron Man and Mandalorian fame), Mike Gunton (Planet Earth II) and Tim Walker (Ice Age Giants). Will it live up to or even exceed the lofty expectations left by Walking With Dinosaurs, and be big enough to sway public perception? We’ll just have to wait and see…

So…does it matter?

At the end of the day, Jurassic World is under no concrete obligation to be realistic. But its creators must surely have recognised they are dealing with the largest dinosaur-related media entity on the planet. That should come with at least some level of awareness and responsibility, especially since the movie that started it all back in ’93 was indeed largely well-researched and hugely influential as a result. 20 years ago(!), Jurassic Park 3 was still taking on new theories about feathers and for 2001 its Spinosaurus looked pretty good (even now I have people on outreach almost refuse to believe it doesn’t look like that anymore, which again demonstrates the franchise’s influence and the changing science simultaneously). Jurassic World’s dinosaurs ended up being rather inconsistent with the franchise’s past approach…by keeping too many things the same.

Perhaps that’s why the flashbacks were added for Dominion, which in their defence do seem to contain some better-looking reconstructions this time round, but at the same time the inaccuracies shown alongside them could be seen as self-defeating. Outside that, Jurassic World’s general disregard for accuracy may not be hurting anyone (depending on how you define “hurt”) and it does provide an in-universe explanation for it, but it still feels like a lot of lost potential. I hope this piece serves to explain to those in Jurassic World’s corner why so many people were disappointed. That it’s a bit more complicated than just saying “it’s only a movie”.

Whether you think the pro-accuracy crowd have been demanding too much, or that Universal were insulting 20 years of hard work in a beloved field of science by wasting its largest public platform, is largely up to you. There are hardliners on both sides and being too factional about it likely won’t help anyone. It’s an issue steeped in subjectivity since, again, being entertainment means Jurassic World doesn’t have to do anything realistically. I and many, many others were saddened that it didn’t, but I won’t berate people for enjoying it as it is. If you are one of the millions of people who love the dinosaurs as they are shown, understand that I’m not saying you shouldn’t. Indeed, I still had fun watching both recent entries (though nowhere near as much as the original obviously), so I don’t want to give the impression that I dislike them as movies. Now that we’re almost three films, a couple of TV seasons and a handful of video games into the new series, the more prominent issue regarding accuracy seems to be their lack of competition.

And of course, Jurassic World will still continue to inspire many people even if it could be much better as palaeontology’s popular ambassador. I have to give kudos to Colin Trevorrow for trying something different this time and acknowledging the issue. I’ll very likely watch it in the cinema anyway, and probably like it as a monster movie as Samuel Welles did. Who knows, maybe this concept of the dinosaurs now being loose in the wild could lead to some funky genetic shenanigans and a new look for the familiar beasts. At any rate, as the saying goes, “let people enjoy things”…

…but also respect valid reasons for others being disappointed.

I applaud the author’s reasonableness about the Jurassic Park franchise. He might enjoy the accuracy in Amazing Dino World from NHK on CuriosityStream.com. Also on CuriosityStream is Ancient Earth II a 3-parter from St. Thomas Production in France. The original name was Prehistoric World, I think.